Until 2014, all of China’s space activities were under the auspices of the government. China Great Wall Corporation (CGWC), founded in 1980, was the only organization authorized by the government to provide launch services. In the 1990s, the corporation worked on commercial projects with American companies (Hughes Aircraft Company). The cost of their launch services was about $30–55 million in 1990. This pricing had a significant impact on the market and was criticized as state-subsidized dumping. From 1990 to 1999, more than half of the Long March rocket launches were for international contracts, accounting for 7-9% of the international market. By the early 2000s, this activity had been discontinued for non-market reasons.

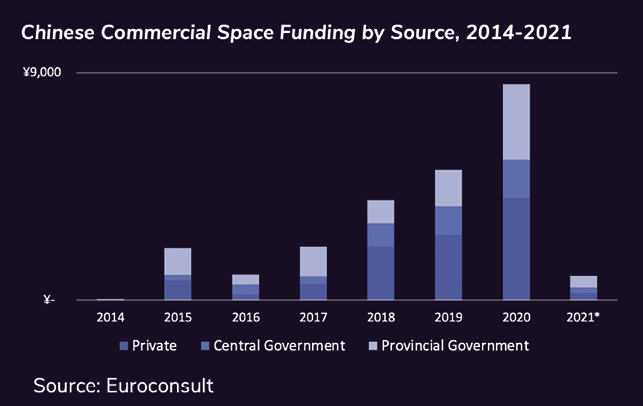

The beginning of the development of Chinese commercial space is usually traced back to the so-called “Document 60,” adopted by the State Council of the PRC in November 2014. The document prescribed “encouraging private capital participation in China’s civil space infrastructure construction,” which gave rise to Chinese space startups. In Europe, the very existence of a private space sector in China is often questioned. However, the existence of private property is enshrined in the PRC Constitution: “==The non-public sector of the economy, including individual and private enterprises operating within the limits established by law, is an important component of the socialist market economy. The state encourages, supports, and guides the development of the non-public sector of the economy, and also supervises and controls it.==” n n To regulate and promote the development of the private space sector, the CNSA established the China Commercial Space Alliance, which includes about 100 organizations, including microchip developer Loongson Technology, rocket developers LandSpace and iSpace, and scientific and technical organizations such as Zhejiang University and Northwestern Polytechnical University. As a result, since around 2017, there has been rapid growth in investment in the “new space” sector. In 2018, several dozen commercial aerospace companies were registered in China. Among them were 36 satellite manufacturers, 22 launch vehicle manufacturers, 39 satellite operators, and 44 satellite application developers. Since then, this number has only grown.

The beginning of the development of Chinese commercial space is usually traced back to the so-called “Document 60,” adopted by the State Council of the PRC in November 2014. The document prescribed “encouraging private capital participation in China’s civil space infrastructure construction,” which gave rise to Chinese space startups. In Europe, the very existence of a private space sector in China is often questioned. However, the existence of private property is enshrined in the PRC Constitution: “==The non-public sector of the economy, including individual and private enterprises operating within the limits established by law, is an important component of the socialist market economy. The state encourages, supports, and guides the development of the non-public sector of the economy, and also supervises and controls it.==” n n To regulate and promote the development of the private space sector, the CNSA established the China Commercial Space Alliance, which includes about 100 organizations, including microchip developer Loongson Technology, rocket developers LandSpace and iSpace, and scientific and technical organizations such as Zhejiang University and Northwestern Polytechnical University. As a result, since around 2017, there has been rapid growth in investment in the “new space” sector. In 2018, several dozen commercial aerospace companies were registered in China. Among them were 36 satellite manufacturers, 22 launch vehicle manufacturers, 39 satellite operators, and 44 satellite application developers. Since then, this number has only grown.

Many startups founded in 2015-2018 began in a similar way: leading engineers or middle managers from the state aerospace industry founded their own companies, recruiting a team of enterprising developers. At one point, this even sparked discussions in the Chinese media about a “brain drain” from state-owned corporations. For example, the founder of Galactic Power previously worked at CALT, the founder of Deep Blue Aerospace, Ho Liang, received his doctorate from Tsinghua University and worked at CASIC, and among the founders of Landsrace is CASC veteran Wang Jianmeng. Venture capital funds, private individuals, and regional governments that wanted to have high-tech manufacturing in their territories invested money in startups.

n For the purposes of this article, Chinese startups can be divided into two large groups. The first group includes companies that develop technology—their own launch vehicles, spacecraft, and satellite platforms. The second group includes companies that provide services—communications, Earth remote sensing, custom imaging, and space data-based services. These deserve a separate discussion, as the topic is vast.

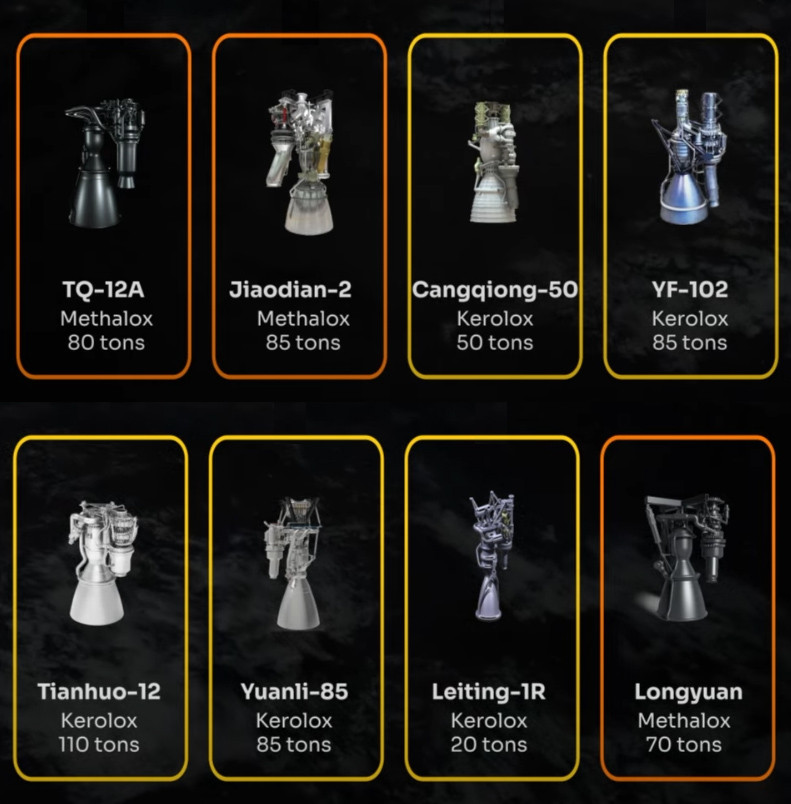

The first rocket startups began by creating simple, mainly solid-fuel rockets, striving to do everything themselves, from engines to control systems. Later, in the second wave of startups, a slightly different approach emerged: the company designs the rocket itself, purchasing components on the commercial market. By the 2020s, this market had become quite developed. For example, the YF-102 engines used in the first stage of the commercial Tianlong-2 and private-public Lijian-2 launch vehicles are purchased from AALPT, a division of CASC, which developed the engine and offers it to private companies. Landspace, in the production of the Zhuque-2 launch vehicle, manufactured 60% of the components itself, purchasing the rest on the market.

The first rocket startups began by creating simple, mainly solid-fuel rockets, striving to do everything themselves, from engines to control systems. Later, in the second wave of startups, a slightly different approach emerged: the company designs the rocket itself, purchasing components on the commercial market. By the 2020s, this market had become quite developed. For example, the YF-102 engines used in the first stage of the commercial Tianlong-2 and private-public Lijian-2 launch vehicles are purchased from AALPT, a division of CASC, which developed the engine and offers it to private companies. Landspace, in the production of the Zhuque-2 launch vehicle, manufactured 60% of the components itself, purchasing the rest on the market.

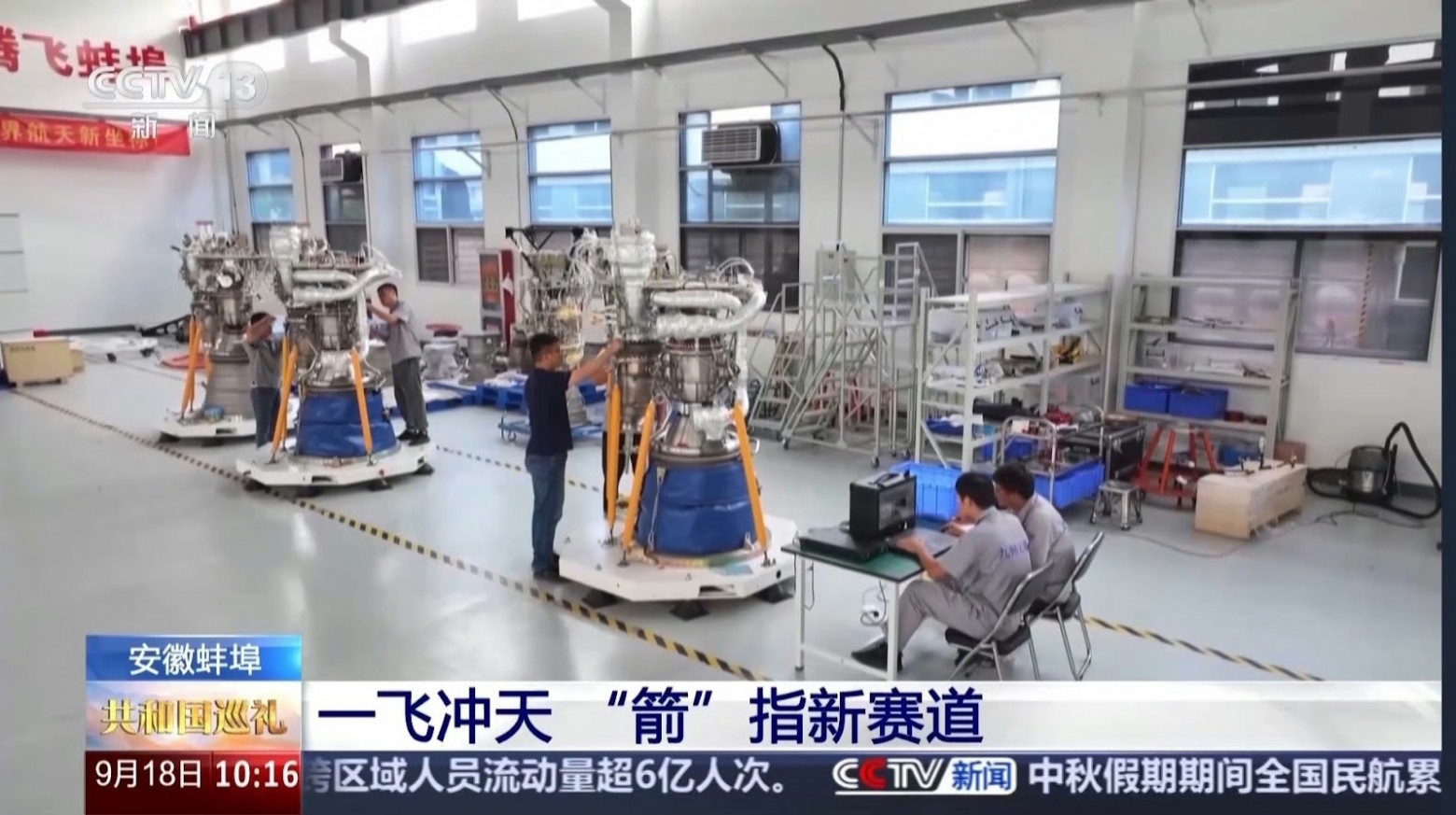

There are also examples to the contrary. The commercial company Jiuzhou Yunjian manufactures Longyun rocket engines. It has signed contracts to supply engines to the startups Rocket Pi and Space Epoch. In addition, the company is developing a 70-ton methane engine for the Shanghai Academy of Space Technology.

Commercial rocket companies

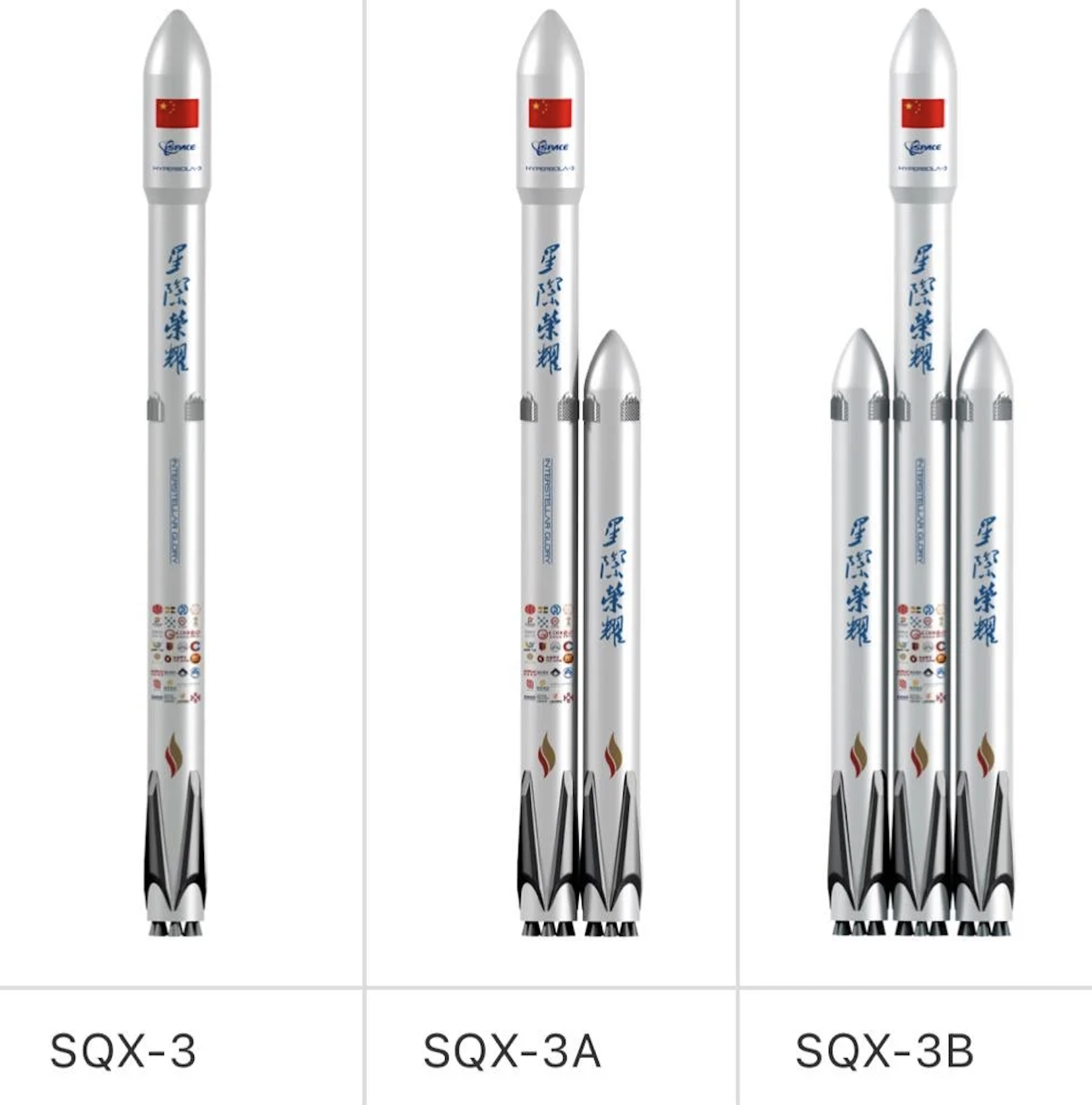

LinkSpace, founded in 2014, was probably the first commercial rocket company. By 2019, the company had built a demonstrator of the New Line-1 rocket, with vertical takeoff and landing. The device performed a jump to a height of 300 meters. But then the company began to experience difficulties. The latest news on the website dates back to 2019, and according to information from Chinese social networks, the startup has ceased to exist. n n The first private rocket was launched into space by i-Space. The startup was founded in 2016 by CALT alumni Peng Xiaobo and Yao Bowen. The solid-fuel Hyperbola-1 (SQX-1, “Shuangqixian-1”) was successfully launched in 2019. It is a lightweight rocket that can carry up to 300 kg of cargo into orbit. After its initial success, the company suffered a series of failures, with three consecutive launches ending in disaster. After a brief hiatus, i-Space resumed launches, but by 2024, only three of seven launches had been successful. Nevertheless, in September 2024, i-Space received $99 million in funding to develop the reusable Hyperbola-3, whose first launch is scheduled for the end of 2025.

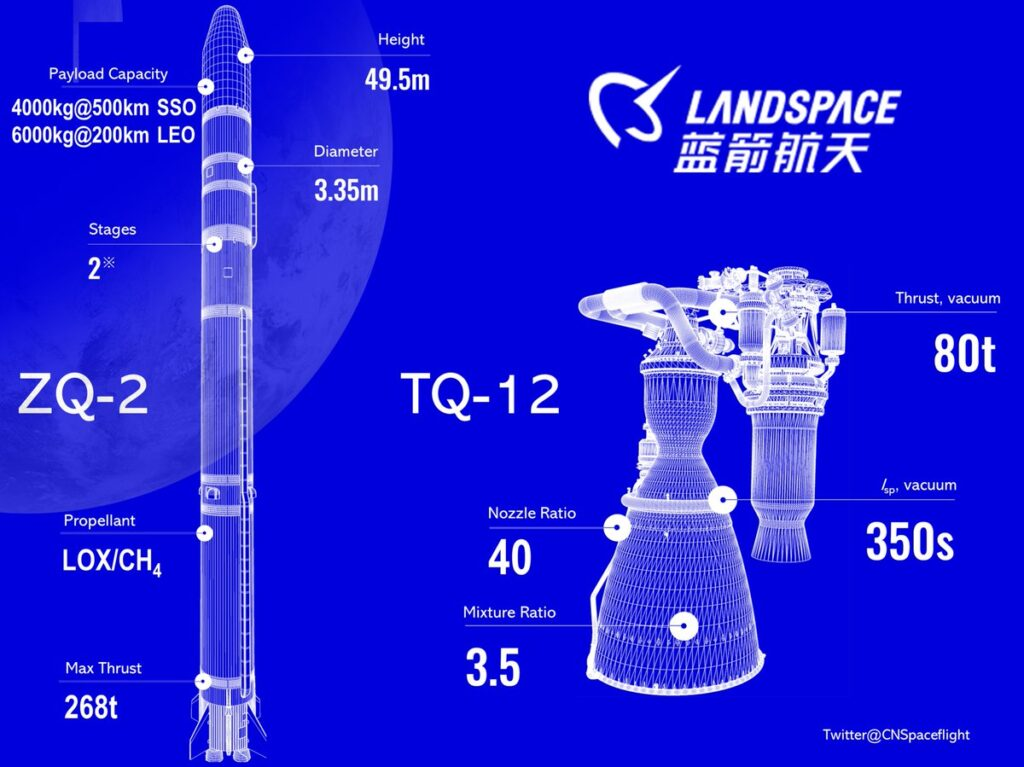

n Landspace (Beijing Blue Arrow Space Technology Co) was founded in 2015. Its founders were Wu Shufan, who had 15 years of experience working at the European Space Agency, Wang Jianmeng, who participated in the construction of the Xichang Space Center, and Kang Yonglai, who later founded Space Pioneer. The company started with the lightweight solid-fuel Zhuque-1, whose only launch was unsuccessful. After that, the startup did not continue to work on solid-fuel rockets, but developed the methane-fueled Zhuque-2. It became China’s first commercial liquid launch vehicle and the world’s first methane-fueled rocket.

n Landspace (Beijing Blue Arrow Space Technology Co) was founded in 2015. Its founders were Wu Shufan, who had 15 years of experience working at the European Space Agency, Wang Jianmeng, who participated in the construction of the Xichang Space Center, and Kang Yonglai, who later founded Space Pioneer. The company started with the lightweight solid-fuel Zhuque-1, whose only launch was unsuccessful. After that, the startup did not continue to work on solid-fuel rockets, but developed the methane-fueled Zhuque-2. It became China’s first commercial liquid launch vehicle and the world’s first methane-fueled rocket.

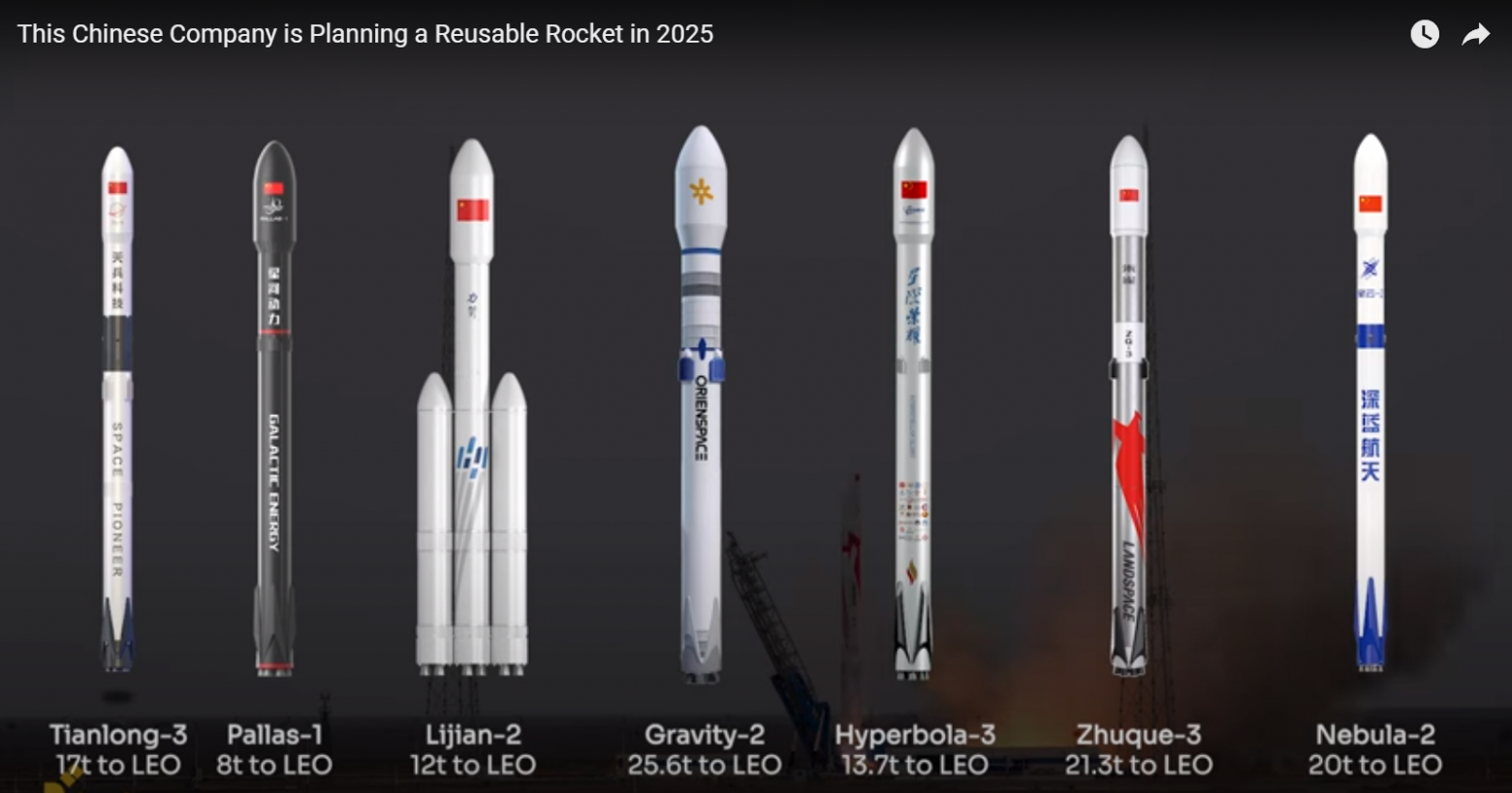

The company with the most launches is Galactic Energy. Its lightweight Ceres-1 launch vehicle has 15 launches to its credit (with one failure). In second place is Hyperbola-1 from i-Space with seven launches and four failures. Space Pioneer, Landspace, and Orienspace have each completed one to three launches. By around 2022, the peak of new company formation had passed, and the commercial launch vehicle sector could be described as crowded. Launch startups are close to providing stable commercial services: rockets have generally gotten rid of their “childhood” problems, and their reliability has begun to inspire confidence among customers and investors. There is no monopoly like SpaceX yet, but a group of leaders has formed, creating launch vehicles with similar parameters.

The company with the most launches is Galactic Energy. Its lightweight Ceres-1 launch vehicle has 15 launches to its credit (with one failure). In second place is Hyperbola-1 from i-Space with seven launches and four failures. Space Pioneer, Landspace, and Orienspace have each completed one to three launches. By around 2022, the peak of new company formation had passed, and the commercial launch vehicle sector could be described as crowded. Launch startups are close to providing stable commercial services: rockets have generally gotten rid of their “childhood” problems, and their reliability has begun to inspire confidence among customers and investors. There is no monopoly like SpaceX yet, but a group of leaders has formed, creating launch vehicles with similar parameters.

In the near future, competition for government and private orders will arise among them. Five companies — i-Space, Galactic Energy, Space Pioneer, Landspace, and Orienspace — have successfully launched their rockets. As of 2024, the most funded rocket startups were Space Pioneer ($552 million), Landspace ($336 million), and Orienspace ($235 million). I am not mentioning three companies here: Expace Technology, China Rocket, and CAS Space, which have operational launch vehicles but are essentially commercial subsidiaries of the state-owned enterprises CASIC, CASC, and the CAS Academy of Sciences, respectively. n  About Chinese names. Commercial companies usually have a Chinese name and an English-language trademark. The same applies to the names of rockets, satellites, and their groups. Therefore, depending on the source, you may read two different news stories 🙂 For example, Beijing Blue Arrow Space (trademark Landspace) should not be confused with Deep Blue Aerospace, which is developing the reusable Nebula-1. Beijing Xinghe Dongli Space Technology Co., Ltd. is called Galactic Energy, but you may also see Galaxy Power. And since the names of the planets are translated into Chinese as a literal translation of the name of the god after whom they are named, Ceres becomes the goddess of grain, Gushenxing. And Ceres-1 from Galactic Energy is 谷神星一号, Gushenxing 1/“Gushenxing-1”.

About Chinese names. Commercial companies usually have a Chinese name and an English-language trademark. The same applies to the names of rockets, satellites, and their groups. Therefore, depending on the source, you may read two different news stories 🙂 For example, Beijing Blue Arrow Space (trademark Landspace) should not be confused with Deep Blue Aerospace, which is developing the reusable Nebula-1. Beijing Xinghe Dongli Space Technology Co., Ltd. is called Galactic Energy, but you may also see Galaxy Power. And since the names of the planets are translated into Chinese as a literal translation of the name of the god after whom they are named, Ceres becomes the goddess of grain, Gushenxing. And Ceres-1 from Galactic Energy is 谷神星一号, Gushenxing 1/“Gushenxing-1”.

The champion here is apparently i-Space (not to be confused with the Japanese i-Space!), which is called Space Honor, Beijing Interstellar Glory Space Technology Ltd., Interstellar Glory, and even StarCraft Glory. Maybe if they spent less time on names and more on rockets, their “Hyperbola” would fly better (joke). By the way, Hyperbola-1 is 双曲线一号, Shuang Quxian-1, SQX-1.

Satellite Companies

Most of China’s commercial satellite manufacturing companies are focused on Earth observation. Since telecommunications and navigation are largely controlled by the state, commercial Earth observation has become the main growth area, whether in terms of production scale, financial value, or investment. In addition, a number of startups are engaged in the creation of specialized application satellites for the Internet of Things, agriculture, unmanned transport for individual companies, and regional-level systems, for example, for cadastral activities or environmental monitoring.

One of the most significant and well-funded companies is Chang Guang (Chang Guang Satellite Technology Co. Ltd), founded on December 1, 2014. It is the first commercial satellite company in the PRC in the field of Earth observation. It is a subsidiary of the Changchun Institute of Optics, Mechanics and Physics (CIOMP) under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The company’s founder, Xuan Ming, previously served as director of CIOMP. CGST claimed to have 1.97 billion yuan (approximately $274 million) in registered capital and, as of early 2024, employed more than 800 people. CGST’s business includes the development of satellites and satellite components, Earth observation products, and the development of UAVs and related systems. But above all, the company is known for its series of Jilin remote sensing satellites.

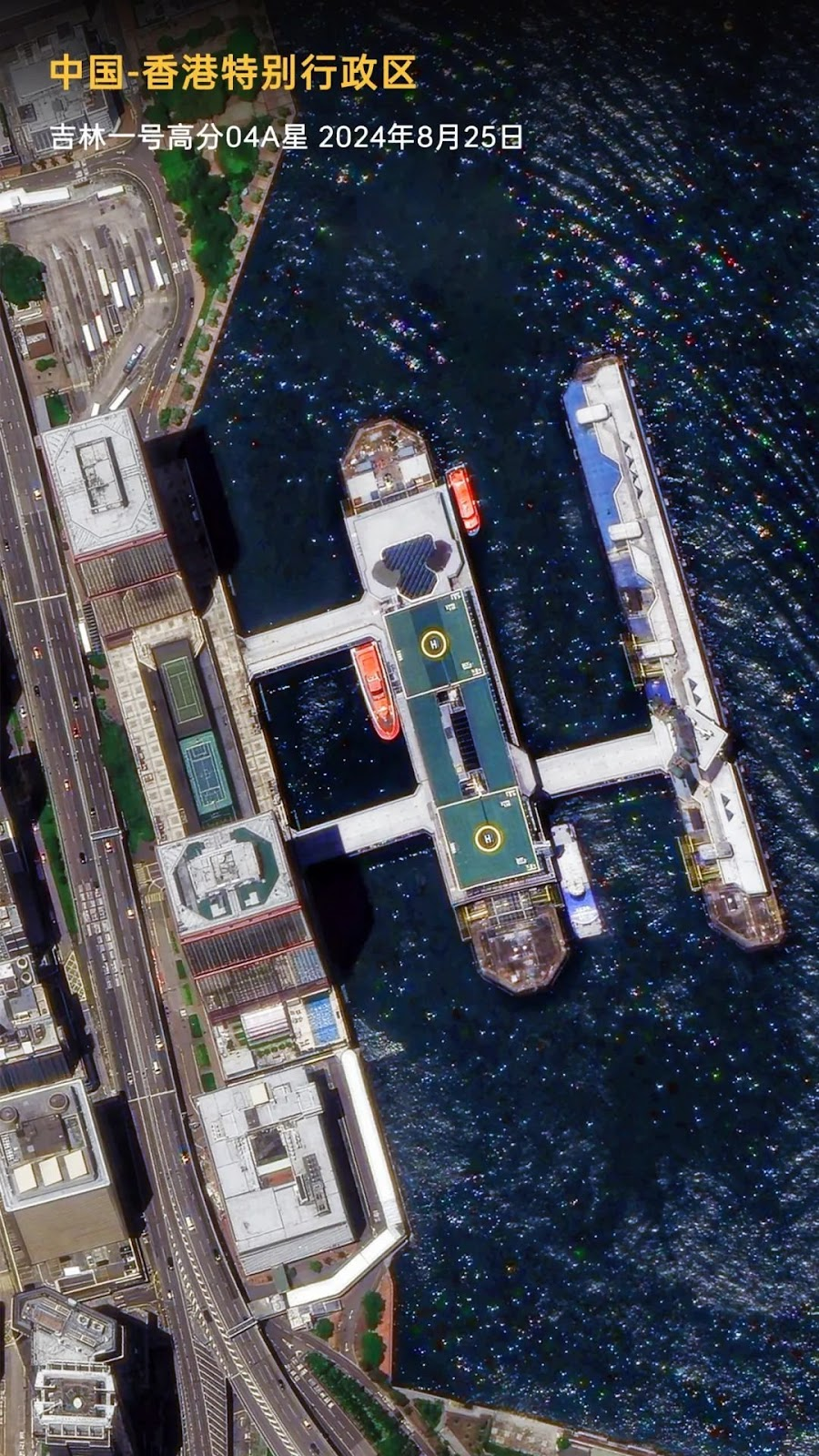

As of 2024, the Jilin-1 constellation already has 115 satellites in orbit, and the share of images with a resolution of 0.5 meters is more than 90%. The satellites can shoot video in high-definition 4K HD format, with real-time control of the camera’s viewing axis to track moving objects (read: surveillance of a country’s naval aviation). A laser communication channel with a speed of 100 Mbit/sec has been implemented to transmit data to the ground and between satellites. Li Deran, professor at Wuhan University and chairman of the Chinese Society of Geodesy and Cartography, says, ==”Thanks to our satellite remote sensing system, if a fire breaks out in a forest, it can be detected in 2 seconds and transmitted to the ground in 13 seconds. In total, the information will be sent to the forest fire terminal in 15 seconds.“== (Replace ”forest fires“ with ”rocket launch sites” and you get a satellite early warning system that can respond in real time.)

https://youtu.be/sQijDuaa1uo?si=2dQaU6Fw3Y3KcY06&embedable=true

Another brainchild of CIOMP is Xian Zhongke Xiguang Aerospace Technology (Siomp Space), a developer of hyperspectral Earth remote sensing satellites. Founded in 2021, Zhongke Xiguang Aerospace is a provider of satellite information services and big data processing services. The company is developing a group of Xiguang series hyperspectral Earth observation satellites:

- XIGUANG-004 (methane emissions monitoring);

- XIGUANG-005 (for agriculture);

- XIGUANG-006 (mineral resources monitoring).

XIGUANG-004 weighs 75 kilograms and is equipped with methane concentration detectors, chlorophyll fluorescence detectors, and a multispectral camera that will help identify sources of methane emissions. It will assist in decision-making in the fields of environmental monitoring and energy. n n Spacety was founded in 2016 by former employees of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. CEO Feng Yang worked at one of CAS’s subsidiaries as a space payload department manager, where he was involved in the system design of the Chinese space station. The company is based in Changsha, with offices in Beijing and Luxembourg. Spacety operates on a “satellites as a service/data as a service” basis. It has no plans to deploy large satellite constellations, but since 2020 has been forming the Tianxian SAR satellite constellation of 96 devices. The company offers a comprehensive approach: production and placement of payloads, launch and operation of satellites in orbit. This allows customers to quickly access space and start providing their own services, testing new technologies, or conducting scientific research. n n ADA Space (Chengdu Guoxing Aerospace Technology Co.) was founded in 2018 and is based in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province in southwestern China. The company plans to create a constellation of 192 Xingshidai (星时代, “Star Era”) satellites. Its formation began with the launch in 2019 of the 10-kilogram Xingshidai-5, which had a 10-meter resolution with a 25-kilometer field of view. Launched in 2021, Xingshidai-10 already provides full-color images with a resolution of 1 meter and multispectral images with a resolution of 4 meters. Xingshidai-15 (2024) tested the functioning of the AI model in orbit. According to the company, technical tests have confirmed the adaptability of the large AI language model in orbit and the reliability of the satellite computing platform. The satellite will use AI to generate remote 3D sensing data in orbit.

n Geely Technology Group, the largest automotive company, through its subsidiaryGeeSpace, intends to form the Future Travel Constellation (未来出行星座) group. GeeSpace satellites will transmit information about the technical condition of vehicles and emergency messages via terminals installed in cars. The satellites will provide two-way messaging and centimeter-accurate positioning. Such positioning accuracy will eventually enable driverless vehicles. They will also give users access to the internet in areas not covered by mobile communications. Launches began in 2022, and by the end of 2024, there were thirty satellites in orbit, distributed across three orbital planes. This configuration provides 24-hour coverage of 90% of the globe, which will enable the launch of communication services for users around the world. The first phase of the constellation, comprising 72 satellites, is expected to be fully deployed in 2025. n n When it comes to the space divisions of large companies, Huawei is also worth mentioning, as it is creating its own low-orbit telecommunications constellation. The telecommunications giant already provides 5G connectivity via satellite, directly from mobile phones, within the coverage area of Tiantong satellites (which covers the whole of China). The service is available through mobile operator China Telecom at a price of 10 yuan per month, and the MatePad Pro 2024 tablet comes bundled with satellite communication services. But Tiantong is a geostationary satellite. The company hopes to create its own 100-gigabit space network in low Earth orbit by 2030.

n Geely Technology Group, the largest automotive company, through its subsidiaryGeeSpace, intends to form the Future Travel Constellation (未来出行星座) group. GeeSpace satellites will transmit information about the technical condition of vehicles and emergency messages via terminals installed in cars. The satellites will provide two-way messaging and centimeter-accurate positioning. Such positioning accuracy will eventually enable driverless vehicles. They will also give users access to the internet in areas not covered by mobile communications. Launches began in 2022, and by the end of 2024, there were thirty satellites in orbit, distributed across three orbital planes. This configuration provides 24-hour coverage of 90% of the globe, which will enable the launch of communication services for users around the world. The first phase of the constellation, comprising 72 satellites, is expected to be fully deployed in 2025. n n When it comes to the space divisions of large companies, Huawei is also worth mentioning, as it is creating its own low-orbit telecommunications constellation. The telecommunications giant already provides 5G connectivity via satellite, directly from mobile phones, within the coverage area of Tiantong satellites (which covers the whole of China). The service is available through mobile operator China Telecom at a price of 10 yuan per month, and the MatePad Pro 2024 tablet comes bundled with satellite communication services. But Tiantong is a geostationary satellite. The company hopes to create its own 100-gigabit space network in low Earth orbit by 2030.

In addition, in 2024, ZTE, Huawei, and Galaxy Space won a tender to build an experimental satellite for mobile phones on the China Mobile network. Founded in 2019, Beijing-based AZSPACE (Ziwei Technology, 紫微科技) is trying to find its niche in the commercial aerospace sector. The startup is developing reusable capsules and related orbital descent technologies. The company offers a platform for microgravity experiments for short-, medium-, and long-term experiments in orbit. On board a small spacecraft, customers can conduct biological experiments, optical observations, or any other research they wish. The equipment is then returned to Earth.

The first space capsule, Dier-1, was launched in December 2023. The next step will be the creation of the B300 light cargo ship. It is available in two versions: the B300-L is non-returnable and can remain in space for a year; the B300-F is designed to return to Earth intact and can operate in orbit for one month. Both versions have a payload capacity of 300 kg. They are designed to conduct scientific experiments that are expected to be in demand by private industry in sectors such as pharmaceuticals, materials science, space biology, etc. Next, it is possible to create a C2000 truck to service the Chinese space station, with the ability to deliver up to 2000 kg of cargo and remove waste.

USPACE Technology Group was founded in 2019 by individuals from Hong Kong’s financial and government sectors. The company’s headquarters are located in Hong Kong and Dubai (UAE). The company offers various satellite components, including an optical camera with a spatial resolution of 50 cm (in panchromatic mode). In addition, it offers Earth observation satellites for purchase at prices ranging from $35,000 to $990,000. n n Other commercial companies include Commsat, MinoSpace, Vastitude Technology, Guodian Gaoke, EllipSpace Beijing Technology, and others.

Component manufacturers

In addition to rockets and satellites, private (and public-private) companies manufacture rocket engines, infrastructure elements, parts, and components for the space market. Lightyear Exploration (Jiangsu) Space Technology is a supplier of structural products, manufacturing 3.8m diameter stainless steel tanks for new launch vehicles. Shandong R.Space (Jiutian Xingge Space Flight Technology) manufactures load-bearing structural elements for launch vehicles: the company’s main products are tanks for storing liquid rocket fuel components, including cryogenic fuel.

n Tanks of various sizes are offered to rocket manufacturing companies. About ten commercial companies are developing engines both for their own rockets and for sale to rocket manufacturing companies. These are Landspace (Tianque-12 methane engine, 80 tons), iSpace (Jiaodian-1, methane, 15 tons in vacuum), Jiuzhou Yunjian (Longyun, 70 tons, methane), Space Pioneer (Tianhuo-11, oxygen-kerosene, 25 tons), CAS Space (Xuanyuan-2, oxygen-kerosene, 80 tons), Orienspaсe (Yuanli-85, oxygen-kerosene, 85 tons), Space Circling (Shaanxi Tianhui Aerospace Technology Co.) manufactures Honglong-1 and Qiaolong-1 kerosene-oxygen engines for commercial launch vehicles.

n Tanks of various sizes are offered to rocket manufacturing companies. About ten commercial companies are developing engines both for their own rockets and for sale to rocket manufacturing companies. These are Landspace (Tianque-12 methane engine, 80 tons), iSpace (Jiaodian-1, methane, 15 tons in vacuum), Jiuzhou Yunjian (Longyun, 70 tons, methane), Space Pioneer (Tianhuo-11, oxygen-kerosene, 25 tons), CAS Space (Xuanyuan-2, oxygen-kerosene, 80 tons), Orienspaсe (Yuanli-85, oxygen-kerosene, 85 tons), Space Circling (Shaanxi Tianhui Aerospace Technology Co.) manufactures Honglong-1 and Qiaolong-1 kerosene-oxygen engines for commercial launch vehicles.

A number of private companies are developing measurement and control equipment for space technology: Aerospace Intelligence, Starlink Measurement and Control (Sound), Shepherd. Back in 2019, there were virtually no commercial companies in China developing laser communication terminals. Several “old” aerospace enterprises (CASC Institute 704, Shanghai Institute of Optics and Fine Mechanics, CASIC) produced such equipment in small quantities for projects such as Beidou, but these were very specific lasers. Since the beginning of 2020, HiStarlink, Laser Link, Laser Starcom, and Shanghai Qionglong Science & Technology have emerged, deploying the production of terminals that will be needed by China’s large non-geostationary constellations. The same applies, for example, to Hall engines and other equipment. n n

When we talk about the commercial space sector, we first think of rockets and satellites. However, the ground segment is often overlooked: how to control these rockets and satellites, how to communicate with them when they leave Earth, and how to manage the data received. The technical means for exchanging telemetry, tracking the position of the spacecraft in orbit, controlling it, and exchanging user data are called the TT&C system. The growth of commercial space in China means that there is a need for more TT&C services.

Commercial companies are launching dozens, and soon hundreds, of commercial satellites per year. Although some of these companies work with state structures (in practice, this is the Xi’an Satellite Launch Center CLTC), this is a rather expensive option. In addition, CLTC has many more pressing tasks. This situation opens up opportunities for commercial TT&C players to emerge. Their business model is usually based on billing satellite operators on a “per pass” basis, meaning that every time a satellite sends or receives data through a gateway, the gateway owner gets paid. This usually ranges from a few dozen to hundreds of US dollars per pass. Considering that each satellite can make several passes per day, the amounts add up to quite a significant sum.

n The two largest companies in this field are Emposat and Tianlian. Emposat (formerly known as Satellite Herd) was founded in late 2016 by a team of former CASC employees. The company has more than 300 employees, and more than half of China’s commercial satellites use Emposat. Its global network of ground satellite stations includes more than 60 ground stations. The company has a number of branches both domestically (in Xi’an, Zhengzhou, Zhongwei), and abroad in the South Pacific, Africa, and South America. In 2020, Emposat established a French subsidiary, SatHD Europe. Today, this subsidiary is believed to manage most of Emposat’s international operations, including the construction of gateways outside China.

Challenges and prospects

Compared to European countries, the development of China’s commercial space industry is still in its infancy and faces a number of challenges. The central government does not provide direct support to commercial companies, limiting itself to licensing activities, while maintaining a generally positive attitude towards this sector. The main players in the public sector, CASC and CASIC, have created their own commercial divisions, which view emerging startups as competitors. Regional administrations are more interested in this sector, as private companies in their territories provide employment, help solve local problems (environment, land use), and shape the technological and innovative image of the region.

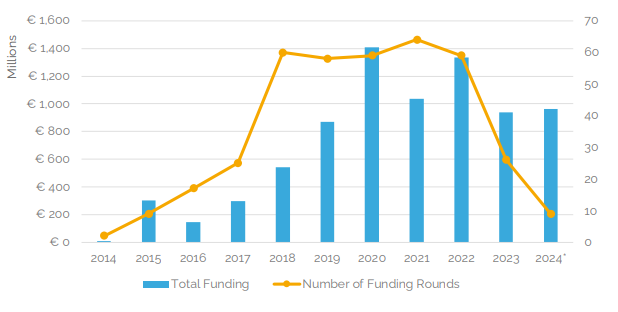

Since 2015, China’s commercial space market has seen rapid growth, averaging more than 20% per year. It was expected that in 2024, the country’s commercial space market would reach 2.34 trillion yuan. According to data from the European Space Policy Institute (ESPI), more than 55 billion yuan (7.5 billion euros at the current exchange rate) has been invested in Chinese space companies over the past decade. Annual funding, which started at €5 million in 2014, peaked at €1.4 billion in 2020, then declined slightly. In 2023, China sent 270 satellites into space, of which 137 (65%) were built by commercial companies. If we take into account private-public companies, then out of 67 launches, twenty (29%) were carried out by commercial rockets.

The main problems facing commercial spaceflight are not technical or economic issues, but rather the lack of legal regulation in this area. For example, while private companies in the US can operate on the principle of “everything that is not prohibited is permitted,” Chinese entrepreneurs have to be more cautious. Policy should clearly define the specifics and limits of what commerce can and should do. There is a need to adjust licensing rules in areas such as satellite communications, D2D communications, and the Internet of Things. The system of internal commercial contracts is based mainly on existing administrative instructions. Disputes arising from the performance of these contracts are usually resolved through consultation with the relevant administrative authorities. The Central Military Commission of the PRC retains a monopoly on issuing permits for commercial rocket launches, which means that private companies cannot conduct business without the blessing of the military. Until recently, all launches were carried out from sites controlled by the People’s Liberation Army.

They are operated and controlled by the General Armament Department, which issues orders regarding the use of missiles and infrastructure at launch sites. The situation is slowly changing, with commercial launch sites being built (in Wenchang and, possibly, in Xichang). The commercial launch complex on Hainan Island is designed to use several types of rockets and is scheduled to begin launches in 2024. In 2019, the country began implementing a sea launch project called the “China Eastern Spaceport.” In 2023, the specialized ship Dongfang Hangtiangang was launched. The ship, 162.5 meters long and 40 meters wide, will be able to meet the needs of small and medium-sized launch vehicles. Commercial rockets Ceres-1 and Gravity-1 are launched from the sea launch site. n  However, a comprehensive space law system has not yet been established. Shen Zhi, deputy director of marketing at China Rocket, said in an interview that ==“the commercial aerospace industry is like a huge machine that is still in its ‘running-in period’ and requires professional maintenance as ‘lubrication’ to ensure its operation.”== Analysts also note insufficient investment and problems with commercializing the results of space activities. For young commercial firms, most of the funding is still mainly spent on research, development, and testing. At the same time, it is worth noting the scarcity of marketing budgets, which depend on investor money. At the same time, the presentation of their projects and plans often boils down to copying computer graphics, which in turn provokes a “copy-paste!” reaction on the internet.

However, a comprehensive space law system has not yet been established. Shen Zhi, deputy director of marketing at China Rocket, said in an interview that ==“the commercial aerospace industry is like a huge machine that is still in its ‘running-in period’ and requires professional maintenance as ‘lubrication’ to ensure its operation.”== Analysts also note insufficient investment and problems with commercializing the results of space activities. For young commercial firms, most of the funding is still mainly spent on research, development, and testing. At the same time, it is worth noting the scarcity of marketing budgets, which depend on investor money. At the same time, the presentation of their projects and plans often boils down to copying computer graphics, which in turn provokes a “copy-paste!” reaction on the internet.

As for the economic success of “new space,” a survey of a dozen and a half managers of commercial space companies was conducted in 2023. The results were published anonymously and showed that most startups have not yet reached self-sufficiency and stable profitability. The head of Landspace said that this point will be reached at 7 launches/year for the Zhuque-2 launch vehicle. Clear economic models for space startups have not yet been formed. It is difficult to demonstrate a path to revenue for such applications of space technology as finance, trade, ecology, and the social sphere. However, this applies not only to China. The “new space” companies themselves see the public sector and large Chinese companies as their primary potential markets and customers. This is not about replacing state-owned space companies, but about supplementing them with products and services that they do not provide (for example, launching small satellites with light launch vehicles).

CAS Space CEO Yiqiang Yang says, “==We position ourselves as a complement to the Long March family of launch vehicles.”== Foreign markets are seen as a desirable but more distant goal. Possible customers in the near term are the Belt and Road countries. ==“The future is bright, but the road is winding,”== says Liu Jian, chairman of China Rocketry Corporation. Overall, in the coming years, some of the companies will likely grow to a critical point where they can generate sustainable profits from launching and operating satellites and integrated systems based on them. Their future depends on Chinese government policy, the growth of the global space sector, and international willingness to engage with China.