This article is not a critique of Agile or Kanban as approaches, nor is it an attempt to prove that IT “does everything wrong.” I’m sharing observations from my own experience working with quality in manufacturing, energy, and later in IT products.

This isn’t about terms and tools, but about how systems thinking is often lost when complex management models are simplified into rituals.

If your processes are already well established and your systems are stable – great. If not, perhaps some of these observations will be helpful.

Quality as a System, Not a Role

When talking to different people about “why QA?”, the answer is usually the same: because it’s easier to get into IT, because there’s less code, there are a lot of course ads, recommendations from friends, and you can start earning money quickly.

Clearly, this person isn’t interested in testing itself. They’re not interested in understanding the product, finding the root cause of errors, or thinking as a user and as a system. For them, QA is simply a backdoor into IT, not a profession. The market makes this very clear today – competition is fierce, but many candidates lack consistency and experience, don’t last long, burn out, or simply disappear after the first few challenges.

QA is not “the easy path.” It’s a separate role that requires attention, logic, and commitment. A good tester is not someone who simply finds bugs, but someone who understood its origins and how they could have been prevented. Sound familiar? Take, for example, any production system; it will inevitably have a quality department/department/management department in one form or another. These departments also employ “testers” and QA engineers who search for discrepancies and the causes of these discrepancies, compiling reports with all the necessary information and assigning them to the developers of these products and documents. I know this because I myself was in this field for over 10 years in various roles, from quality engineer to department head and technical auditor. When I transitioned from industry to IT, I had a strange sense of déjà vu: the people are different, the terminology is different, the tools are modern – but the problems… are the same:

“We didn’t take this into account.” “Let’s fix it quickly.” “The main thing is not to blame someone, but to make sure it works.” “We’ll figure it out later.”

The only difference is that in industry, a mistake could cost millions of dollars or lives, while in IT, it often also costs money, reputation, and the team’s nerves. The logic is similar, and the funny thing is: all of this has long been documented. n Deming, Shewhart, Taiichi Ohno, and Ishikawa – the people who solved these problems 30–60 years ago – and today, most QA practices in IT are simplified and out-of-context versions of their ideas.

Lean, Kanban, Flow, Value Stream, WIP, Muda, Agile – they sound solid and modern. The problem is that these words often lack a system. All that’s left are rituals, boards, and meetings, but the meaning has been lost.

Pull vs. Push Manufacturing Methods

The term Kanban has a literal translation from Japanese: “Kan” means visible, and “ban” means card or board. The card is the only similarity between IT and Lean manufacturing. Not everyone agrees, so let’s explore.

Let’s imagine a car, composed of various components and parts, assembled at a factory and delivered to a dealership, like dozens of other cars. When a customer picks up the car, a gap forms in the warehouse – a shortage of one car. The dealership sends a signal to the factory indicating how many cars and in what configuration it needs to replace. This is the amount that needs to be replenished. The factory ships the car from the warehouse to the dealership, and now the gap is already in the warehouse. Intermediate stages of car assembly receive signals from the warehouse, and so on, until the very beginning of the chain. Until signals arrive, the assembly line must stand still. It should not produce more cars than necessary. Each subsequent stage assigns a task to the previous stage, passing a card with the task and the specific configuration. Thus, the entire assembly line completes one cycle, and the final Kanban arrives at the materials warehouse to receive everything necessary to begin production of the new car. This pull-based system was developed by Taiichi Ohno at Toyota.

In physical production, we have an object at the end, and to reproduce it, we must go through all the production stages again. In IT, you don’t have to rewrite the code every time you want to sell it. You don’t have to rewrite the operating system every time you sell a computer, but the computer itself must be completely manufactured each time, from circuit board production and metal mining to assembly in China. That’s why there’s excess profit in IT: you make a single product, but when you sell it, it multiplies into as many copies as needed, eliminating the need to “build hundreds of cars for the warehouse”.

In IT, production is often push-based, from start to finish: DevOps doesn’t assign tasks to testers, testers don’t assign tasks to developers, and developers don’t define requirements for analysts. You can’t have a ready-made website, ready-made code, or ready-made user story and wait for the client to immediately hand it over to them and immediately do the same thing we just gave them – this is the whole fundamental difference; this is closer to push systems.

In practice, this is expressed simply: in a push approach, a team has 15–20 active tasks at a time, of which only 3–4 are actually moving forward. In a pull approach, there are fewer tasks, but they are completed faster and with fewer backtracks.

Many who claim to use Kanban actually move cards around on a board, but the system remains unchanged. People begin to oversimplify the tool: a board with cards visualizes the work process instead of managing data-driven development. Without sufficient reliable data, estimating task time is like reading tea leaves. Cause-and-effect relationships, statistics, and specific resource requirements are somehow discarded and relegated to the background.

Of course, many teams successfully use WIP ( Work in Progress ) – limits and flow metrics – and this is already a step towards real Kanban , although I have never encountered either it or Scrum in its pure form anywhere, but a mixture of frameworks due to frequently changing or incorrectly built processes is a common occurrence.

This is where confusion often begins. Kanban, as part of an industrial flow management system, is replaced by the Kanban board as a visual tool, and then imperceptibly blended with Agile practices. As a result, what’s being discussed is no longer a quality and flow management system, but a set of convenient rituals that are supposed to somehow work.

When Do Practices Become Rituals and Where Do We Deceive Ourselves?

Many buzzwords are trendy – Agile, Lean, Kanban, Muda, Mura. Personally, they sound like a cult to me: they have little practical meaning, and there are more understandable equivalents. This was fashionable 10-15 years ago, for the sake of exoticism, to attract attention. We simply take a system that has been around for 20 years and use it without introducing anything new over time. Some employees are resistant to such implementations, but we need to engage them because it’s easier for people to communicate in a common language. Perhaps this will work for top management, as a kind of know-how.

Some people often use Agile as a ritual rather than a system of thought, ignoring decades-old industrial approaches to quality. Agile originally emerged as a response to heavy, rigid processes. n And it did deliver: flexibility, speed, and feedback. But in reality, Agile in development often turns into the following:

- The requirements are recorded superficially (“we’ll clarify them later”),

- Complex scenarios are postponed (“not in this sprint”),

- Defects are accepted as the norm (“Well…it happens”),

- Retrospectives and daily reports end with general conclusions

For example, a feature has passed all stages of development, testing, and release, but after a few days, user complaints are coming in, transactions aren’t processed, and support takes a long time to investigate the issue. Formally, the bug was quickly fixed with a hotfix. The reasons could have been in the code, incomplete testing, or in the requirements, which were insufficiently described and allowed for multiple interpretations. Agile doesn’t forbid this – it simply doesn’t require teams to prevent it.

Another example: A QA is looking for a way to automate monotonous processes. Initially, they test manually to familiarize themselves with the system, understand the environment, and understand behavior patterns. Time passes, urgent tasks continue to fall, and there’s simply no time for automation. A highly qualified and highly paid employee becomes mired in routine and ends up doing work they weren’t hired for. Or, take a simplified version, where the QA simply performs testing work, without influencing processes or improving them. From the outside, this all looks like another trend: yes, we have professionals, but they’re clearly doing the wrong thing. Every action should have value, and if it brings minimal or no value, it needs to be eliminated or made more efficient.

Agile Retrospective vs. Industrial Root Cause Analysis ( RCA )

An Agile retrospective often looks like this:

- What went wrong?

- What can be improved?

- What are we going to do next time?

Industrial RCA asks tougher questions:

- Where exactly did the system fail?

- What protection was missing? Or could have been?

- Why was this defect able to reach the user?

- What is necessary to ensure that it does not happen again?

The difference here is fundamental: Agile often improves human behavior, while an industrial approach improves system behavior. In my opinion, in fintech, the latter is often far more critical. Fintech isn’t a place where “we’ll fix it later,” and that’s why practices developed decades ago for factories suddenly prove more modern than they seem. Let’s compare:

Agile without an industrial mindset of quality fuels chaos. For example: Features are released quickly, metrics are growing, but the data is varied and inconsistent; releases are frequent but unstable, as Agile has accelerated flow and decision-making.

Agile with an industrial foundation creates reliable systems by leveraging the best of both worlds. In this case, releases are fewer but more stable, with root cause investigations, data quality control, and less firefighting.

And will be exceptions when a company intentionally creates a product or develops a dubious quality for the sake of other advantages: being first to market and establishing itself, or acquiring a large customer base while competitors perfect their developments. Elon Musk, for example, has launched numerous rockets, improving them with each iteration after launch. The key is to make these decisions consciously and remember to improve and fine-tune products and processes in the future.

Quite reasonably, questions may be raised about the inappropriateness of comparing industry and IT. In IT, resource expenditure on tasks can vary enormously, as they can range from large to small, all dictated by market demands. In an industry with mass production, many processes are repeated, meaning they are standardized, and variability is small. However, if it does occur, it can be optimized and fine-tuned. Development forecasting is possible with a probabilistic approach, but it requires statistics, as IT is full of new and unpredictable processes, often comparable to research. So, what can we do in this situation? And what can we learn from industry?

- Quality as a management function

This is the responsibility of the entire company, the entire team, not just QA . If every department and employee within it performs their work fully, on time, and in accordance with requirements, then their client—and any adjacent department or colleague is still just that, a client, but internal – will begin their part of the work much more quickly, with a lower risk of non-compliance. QA no longer acts as the sole filter at the very end of the process. This sounds something like, “We have brakes, so we can accelerate without looking back,” or “We have firefighters, which means we can build a house out of cardboard.” Testing, no matter how frequent and thorough, does not guarantee 100% quality. If a defect regularly reaches testing, it means it has been in the system for a long time, and the tester is simply the last person to notice it.

How can this be influenced? Even a few team meetings discussing the inputs and outputs of processes will significantly simplify the work of the entire development team. Every department, not just QA, manages risks and makes decisions for the release, shaping quality gates.

- The 5 Whys Method

The “5 Whys” method is popular in IT, but it is often used as if the goal is to find someone to blame.

For example, an incident: users cannot pay for an order.

Poor analysis: why? – bug. Why? – overlooked. Conclusion: “QA, be more attentive”.

Congratulations, the system hasn’t changed at all. It’s very easy to stop at “Didn’t test it, forgot about it,” but it’s harder to ask the next question: “Why did the system allow it not to be tested?”

In a thorough analysis of the incident, we came to the conclusion that: requirements were frequently changing and were not reviewed, and responsibility was blurred between teams.

The correct conclusion: don’t “be more attentive,” but change requirements and processes, remembering to promptly inform all participants and share the method’s application experience with less experienced colleagues and newcomers. One example is about improving processes and quality gates was described above.

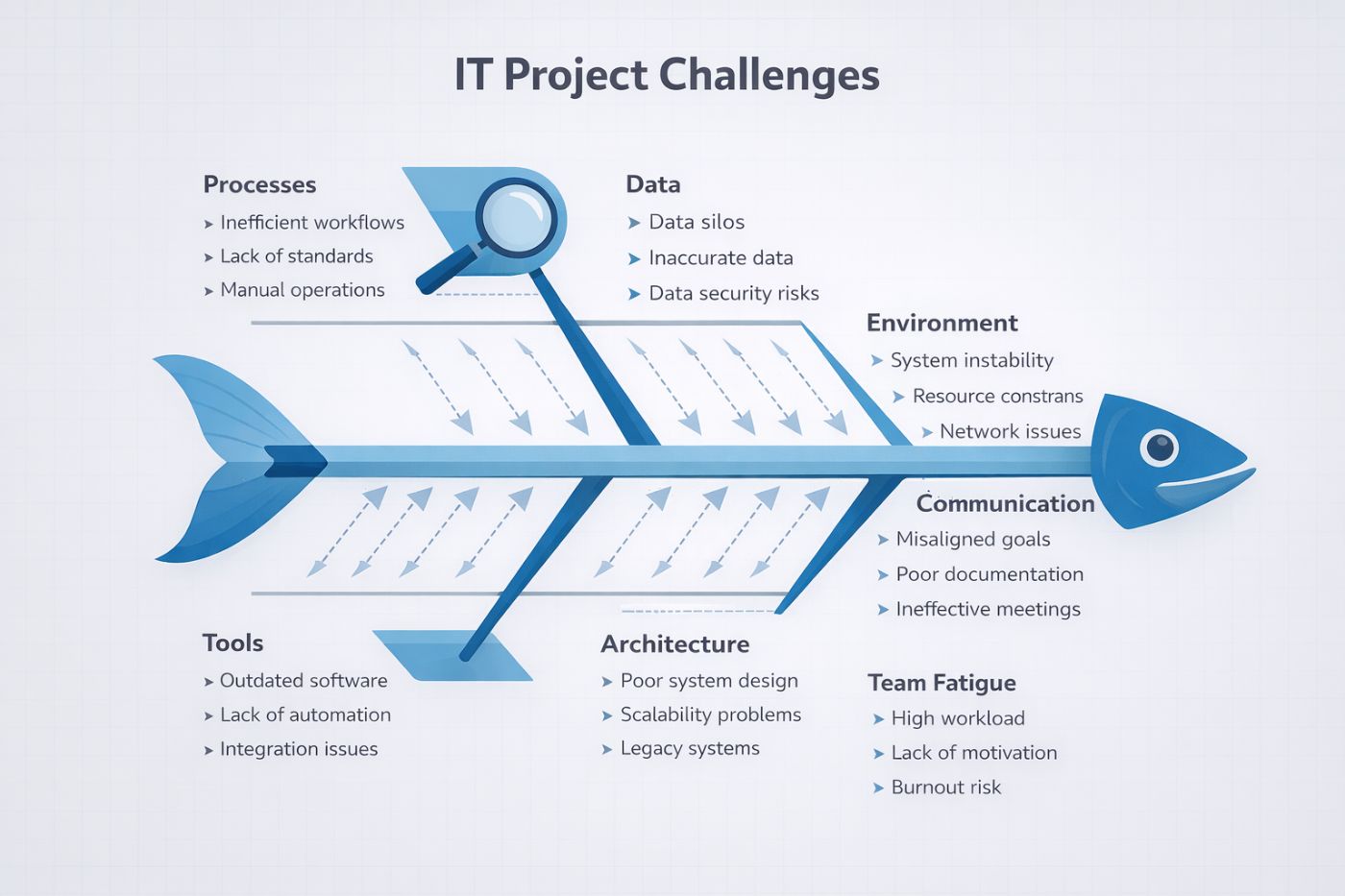

- Ishikawa diagram ( Fishbone )

An excellent tool for examining a problem from multiple angles simultaneously: processes, tools, architecture, data, environment, communications, and team fatigue.

For example: if an automated test fails at night, the real cause is often in the data/environment, not the test itself.

- 5 S

Order is not about aesthetics or tidiness on the table, but about speed and reliability in work. In IT 5S, these are: repositories and documentation, test data, environments, dashboards, Jira / Confluence.

Example of 5S for QA:

1) Sort: remove dead test cases and duplicates

2) Set in order: unified test case/ checklist template + tags

3) Shine: Regular cleaning of test data

4) Standardize: standards in the specification with clear criteria

5) Sustain: stability thanks to automatic checks in CI

Disorder in tests creates noise, and noise increases the risk of missed defects.

-

Waste and Lean

If you translate “Lean” literally, it sounds like “thin,” because the method eliminates all unnecessary operations, inventory, and expenses. However, some people misinterpret this as cutting corners, slashing budgets, and laying off employees. This might work two or three times, but then there’s no one to cut and nothing to cut. In reality, defects discovered late are the most costly and represent a huge loss.

Taiichi Ohno talked about 7 types of waste (muda). If you translate them into IT language, it will sound very familiar.

Losses in IT:

1) Waiting – QA is waiting for the environment, access, and data

2) Reworks – Bugs found after release

3) Extra work – unnecessary, irrelevant checks

4) Queues – backlogs of bugs that no one ever comes back to.

5) Movements – manual regressions by clicking on one scenario

6) Redundancy – 5 matches of one field

7) Defects – a surprise in production

Not long ago, an eighth type of loss was added, and this is unrealized human potential, talent.

Conclusion

Below is a simplified comparison that I’ve repeatedly observed when applying industrial quality principles in IT teams.

| Industrial approach | IT approach |

|—-|—-|

| Data-driven and constraint-based flow control | Managing tasks through statuses and meetings |

| Early detection of defects | Post-release bug fixes |

| Root Cause Analysis (RCA) | Quick fixes and disassembly for retro |

| Work in Progress (WIP) Limit | Executing the maximum number of tasks in parallel |

| Quality is the responsibility of the entire system | Quality is the responsibility of QA |

| Improving system behavior | Improving people’s behavior |

| A defect is a signal of a problem in a process. | Defect is a working inevitability |

This contrast explains why some teams move fast but burn out, while others move more slowly but stay predictable.

I’ve applied these approaches in practice with IT teams with weekly releases, where early defect detection, root-cause analysis, and limiting work-in-progress helped reduce incidents, speed up releases, and ease the workload on teams. Going into those cases would require a separate article, but they demonstrate that industrial quality principles remain relevant in digital products. The key insight is not that industry is better than IT, but that many reliability problems in modern software teams stem from losing system-level quality thinking – something industry solved decades ago, and that can be consciously reintroduced without abandoning Agile.