On Friday evening, February 6, 2026, at around 7 p.m. Seoul time, an employee at Bithumb, South Korea’s second-largest cryptocurrency exchange, was processing payouts for a promotional campaign. Winners were supposed to receive 2,000 Korean won (about $1.37). Instead, the system credited 2,000 bitcoin.

Within minutes, 620,000 BTC appeared in customer accounts across the platform, nearly 3% of Bitcoin’s entire 21 million supply.

https://x.com/conorfkenny/status/2020801266230690267?s=20&embedable=true

At market prices, that was $44 billion. For context, Bithumb’s actual Bitcoin reserves at the end of Q3 2024 were 42,619 BTC. The exchange had just credited users with 14.5 times more Bitcoin than it actually held.

Some users logged in, saw life-changing balances, and did exactly what you’d expect: they sold.

About 1,788 BTC hit Bithumb’s order books before the exchange froze affected accounts. Bitcoin’s price on the platform crashed 17% in minutes, briefly touching 81 million won ($55,000) while other exchanges traded normally above $68,000. By 7:40 p.m., twenty minutes after it started, Bithumb had restricted trading and begun clawing back the phantom balances.

https://x.com/lookonchain/status/2019751187646402923?s=20&embedable=true

The blockchain never moved. No on-chain transactions occurred. Bitcoin’s global supply stayed at 19.6 million, exactly where it had been all day.

And yet, for twenty minutes, $44 billion in Bitcoin that didn’t exist traded on a live exchange in front of real users executing real orders at real prices.

The incident was contained. Bithumb says it recovered 99.7% of the credited BTC and covered the remainder with its own funds. Prices normalized. Markets moved on. South Korean regulators launched an emergency task force. Nobody lost money permanently.

But the thing that broke isn’t fixed. And the implications go far beyond one exchange in Seoul.

What Actually Broke?

This wasn’t a hack.

Nobody breached Bithumb’s systems. No private keys were stolen. No malicious code was executed.

The error was humiliatingly simple: a promotional script was supposed to credit rewards in Korean won. An employee configured it to credit Bitcoin instead, and typed “BTC” where “KRW” should have gone. The numeric value 620,000 stayed the same. The unit changed.

What’s remarkable isn’t the human error. People make typos. What’s remarkable is that the system let it happen at all.

Bithumb’s internal ledger, the database that tracks what users see when they log into their accounts, accepted the entry without question.

- It didn’t check whether the exchange actually held 620,000 Bitcoin.

- It didn’t flag that the amount being credited exceeded the platform’s entire reserve.

- It didn’t require secondary approval for distributing $44 billion in assets.

It just… wrote the balances into the database and displayed them to users as if they were real.

And for twenty minutes, they were real enough to trade.

This is the part most people miss. The Bitcoin that appeared in those accounts wasn’t “fake” in the way a Photoshopped screenshot is fake.

From the perspective of Bithumb’s trading engine, those balances were legitimate. Users could place sell orders. The order book matched them with buy orders. Trades executed. Prices moved. The market reacted to the supply that existed only in a database, not on the blockchain.

South Korean lawmaker Na Kyung-won described it plainly, according to local media: if an exchange credits figures in its internal ledger without any corresponding movement on the blockchain, it is effectively selling assets it does not possess.

That’s not a technical bug. That’s a structural design flaw.

The Samsung Securities Shadow

This isn’t South Korea’s first rodeo with phantom assets created by input errors.

On April 8, 2018, Samsung Securities, one of the country’s largest brokerages, tried to pay dividends to 2,018 employees in its stock ownership program. Each employee was supposed to receive 1,000 Korean won, worth about $0.93 per share. Instead, an employee entered the payout as 1,000 shares per person.

The system issued 2.83 billion shares.

That was 30 times Samsung Securities’ total market capitalization. The phantom shares were worth about 112.6 trillion won, roughly $105 billion on paper.

Thirty-seven minutes passed before the firm detected the error.

In that window, 16 employees sold millions of shares despite repeated warnings from management. Those sales hit the Korea Exchange’s settlement system, spreading the error beyond the company and into the broader market. Samsung Securities’ stock price collapsed 11% in a single day.

The National Pension Service, South Korea’s largest institutional investor, immediately suspended all trading with the firm. The Financial Supervisory Service launched a formal investigation and ultimately barred Samsung Securities from opening new client accounts for six months.

The parallels to Bithumb are obvious. Both cases involved promotional payouts where an employee confused a currency unit with an asset. Both created “ghost balances” that vastly exceeded the firm’s actual holdings. Both resulted in immediate selling and sharp price crashes.

But there’s a critical difference that makes the Bithumb case more structurally concerning: Samsung Securities’ error entered the external settlement system tied to the Korea Exchange and the Korea Securities Depository. That meant the mistake propagated beyond Samsung’s internal ledger and infected the broader market infrastructure.

Bithumb’s error stayed inside its own database. The platform never settled those balances on the blockchain, so the error remained contained within the exchange’s four walls.

That containment is why Bithumb’s incident resolved faster and caused less systemic damage.

It’s also why it exposes a deeper problem: centralized exchanges operate on internal ledgers that can diverge from on-chain reality without anyone outside the exchange noticing until something breaks publicly.

The Ledger Problem: Why Centralized Exchanges Are Banks That Print Their Own Money

Here’s what most users don’t fully understand about centralized exchanges.

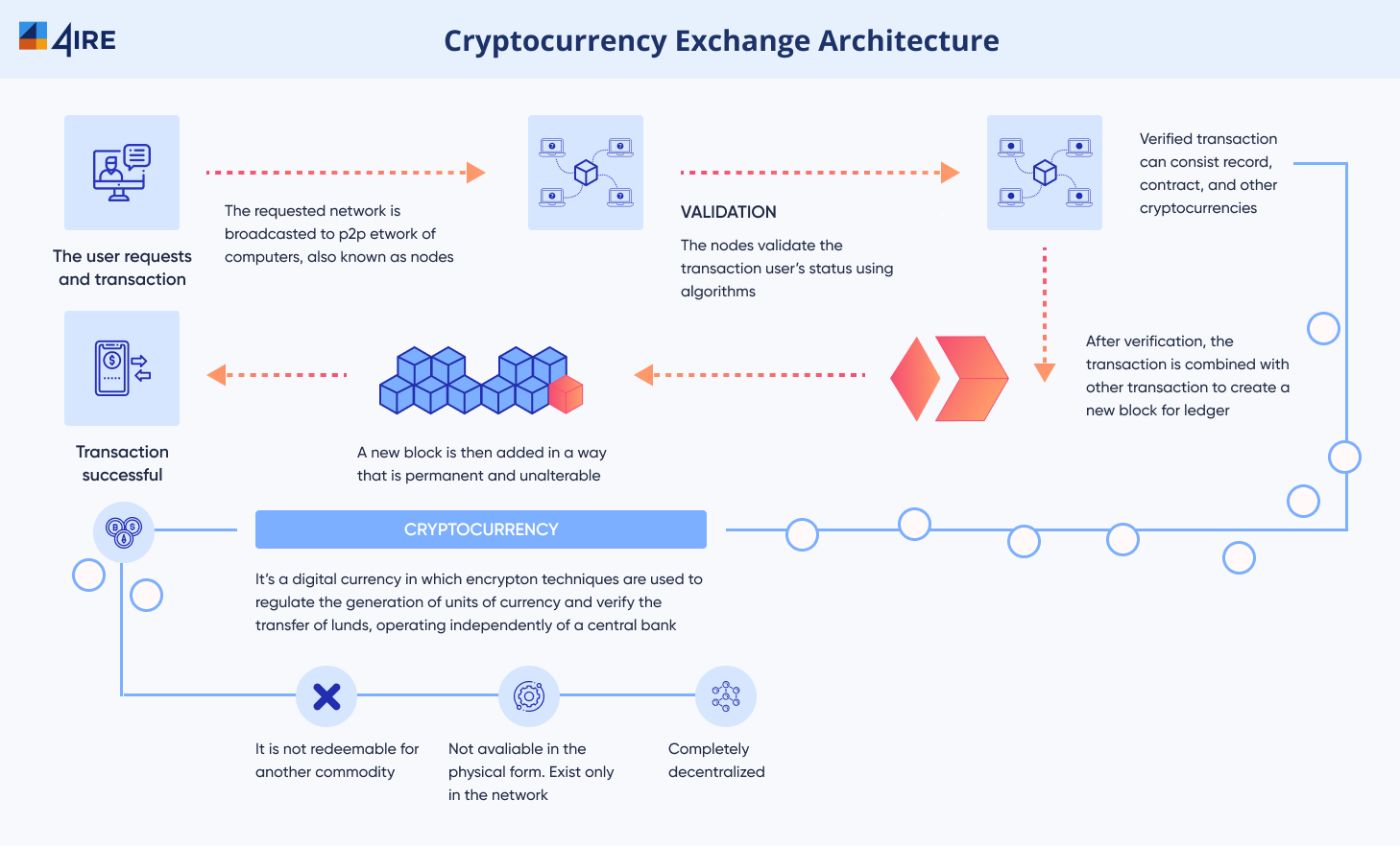

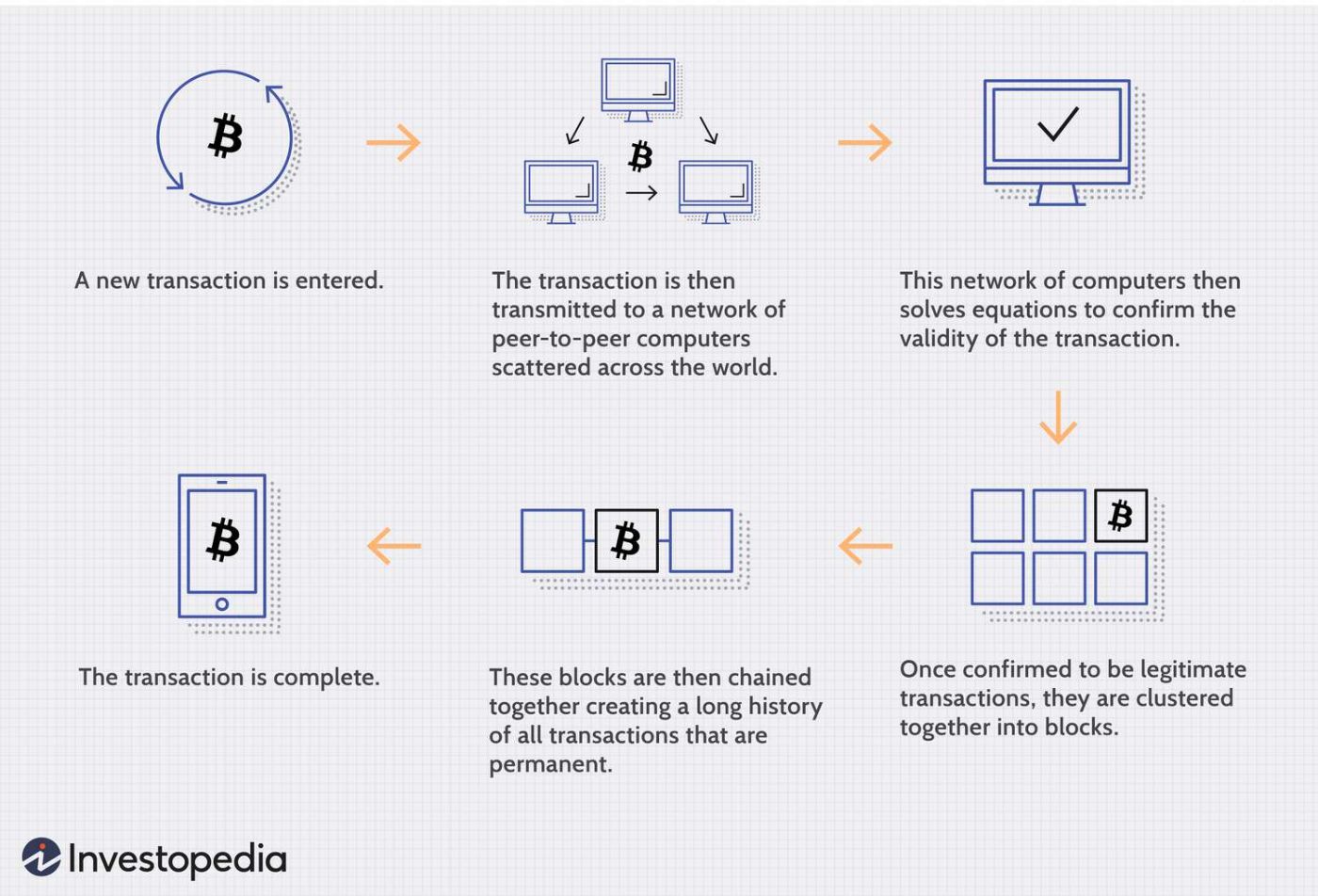

When you deposit Bitcoin to Coinbase, Binance, Kraken, Bithumb, or any other CEX, the Bitcoin moves on-chain to an address controlled by the exchange.

That’s a real blockchain transaction. But once it arrives, the exchange doesn’t track your specific coins on the blockchain anymore. Instead, it credits your account in its internal database.

From that point forward, when you log in and see “0.5 BTC” in your account, you’re not looking at Bitcoin. You’re looking at a database entry. A promise. An IOU. The exchange says it owes you 0.5 BTC. Whether it actually has 0.5 BTC sitting in reserve to back that claim is something you have to trust.

When you trade on the exchange, buying, selling, or swapping between assets, none of that touches the blockchain. It’s all database updates.

The exchange adjusts numbers in its ledger. Buyer’s balance goes down, seller’s balance goes up. No on-chain settlement. No gas fees. No public record.

The blockchain only comes back into play when you withdraw. That’s the moment the exchange has to prove it actually holds the Bitcoin it claims to owe you. It initiates an on-chain transaction from its reserves to your wallet.

If the exchange doesn’t have the Bitcoin, the withdrawal fails. But as long as you’re not withdrawing, the exchange can run a ledger that shows balances far exceeding its actual reserves, and nobody outside the exchange knows.

Bithumb just demonstrated this at a scale nobody expected. The platform held 42,619 BTC. Its internal ledger briefly showed 620,000+ BTC in customer balances. That’s a 14.5x mismatch.

And the system didn’t stop it.

Independent researcher Shanaka Anslem Perera, who works at the intersection of monetary theory and systems design, put it bluntly on February 8: “$44 billion in Bitcoin that never existed just traded on a live exchange for 20 minutes and the entire market is drawing the wrong conclusion.”

The conclusion people drew was “Bithumb made a mistake and fixed it.” The conclusion they should draw is “centralized exchanges can credit balances they don’t have, and those balances become market-active until someone notices.”

The Regulatory Reckoning

South Korean regulators did not treat this as a minor operational hiccup.

On February 7, the Financial Services Commission (FSC), Financial Supervisory Service (FSS), and Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) held an emergency inspection meeting.

FSS Governor Lee Chan-jin announced on February 9 that the agency would launch targeted probes into “high-risk areas” across the virtual asset market, with a specific focus on exchanges’ internal control systems, IT infrastructure, and ledger management practices.

Lee was explicit: the Bithumb incident exposed “structural weaknesses in virtual asset information systems” that fall outside the current regulatory framework. The FSS is conducting an on-site review of Bithumb to determine the precise cause, assess the exchange’s safeguarding of customer assets, and evaluate whether its systems are sufficient to prevent recurrence. If the inspection uncovers legal breaches, the review escalates to a formal investigation with strict enforcement measures.

Critically, Lee signaled that unresolved weaknesses in internal controls and IT systems could eventually translate into licensing risks for exchanges. That’s not a slap on the wrist. That’s a threat to operating licenses.

Regulators also made clear this won’t stay confined to Bithumb.

The inspection could expand to other exchanges if irregularities are identified, and the FSS plans to incorporate findings from the Bithumb review into South Korea’s second phase of virtual asset legislation, the regulatory framework that will govern crypto platforms going forward.

The tone from lawmakers was sharper. Kim Jiho, a spokesperson for the ruling Democratic Party, called the incident a revelation of “structural weaknesses in internal controls and ledger management systems of cryptocurrency exchanges” that go beyond a simple input error.

Lee Chan-jin’s framing in a February 9 press briefing was particularly telling. He described the incident as a case of “unjust enrichment” requiring restitution, and noted that users who sold the ghost Bitcoin are legally obligated to return the assets even if they genuinely believed the funds were theirs.

The legal basis: Bithumb’s promotional materials explicitly stated rewards would range from 2,000 to 50,000 won. Recipients of 2,000 BTC could reasonably have known the funds were not rightfully theirs.

Bithumb is now in the uncomfortable position of pursuing individual users for asset recovery.

The exchange says it has recovered 99.7% of the credited Bitcoin, but approximately 125 BTC worth about 13 billion won remain outstanding.

Of that, roughly 3 billion won has already been withdrawn to customers’ bank accounts, and another 10 billion won was used to purchase other virtual assets on the platform.

An exchange official confirmed Bithumb is contacting users individually to “seek repayment through voluntary cooperation on a case-by-case basis.” If that fails, the next step is civil lawsuits seeking restitution of unjust gains. That legal confrontation appears unavoidable.

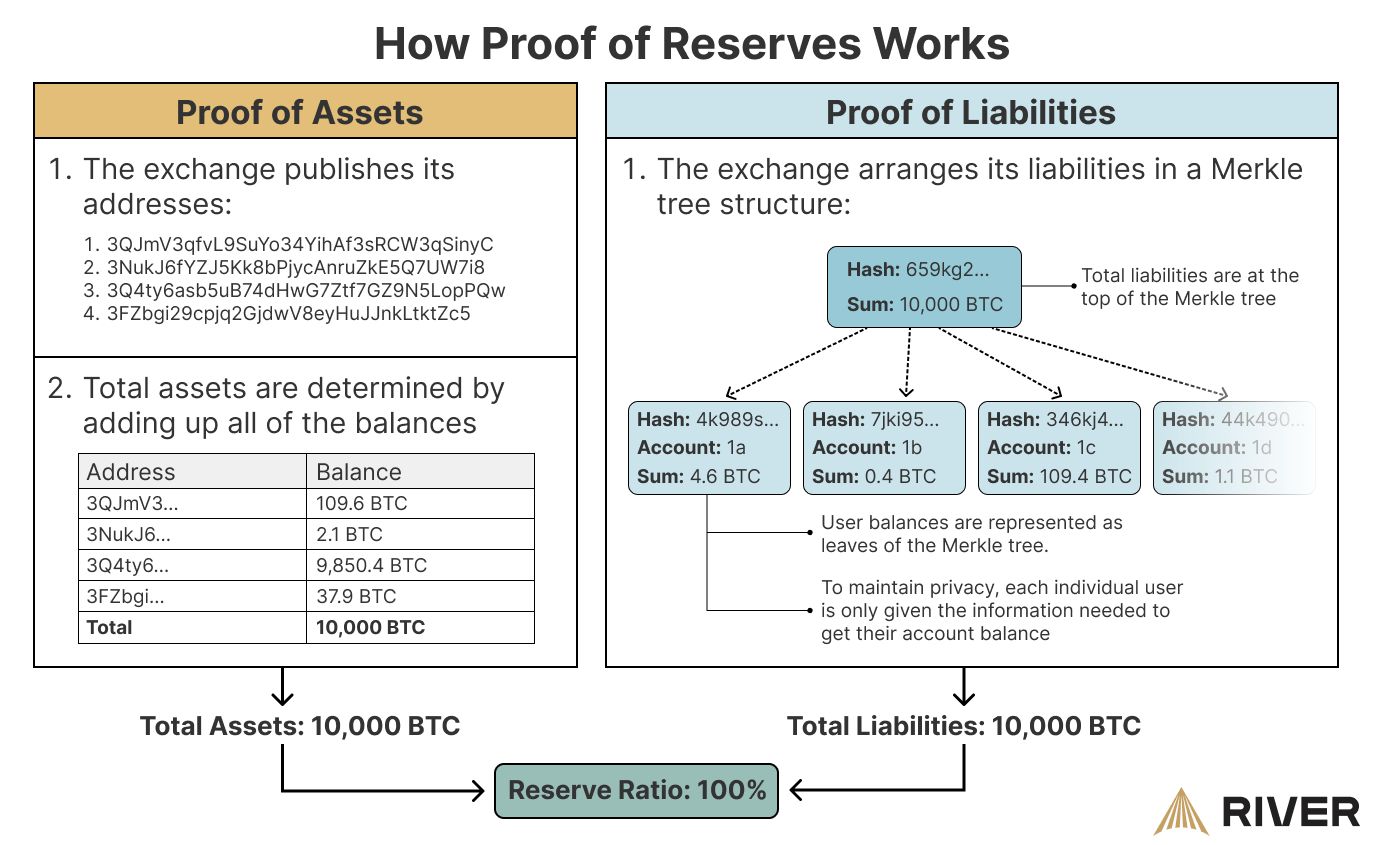

Why “Proof of Reserves” Isn’t the Answer

After FTX’s collapse in 2022, the industry rallied around Proof of Reserves as the transparency fix.

Exchanges now publish cryptographic attestations proving they control sufficient on-chain reserves to cover customer liabilities. Platforms like Kraken have been doing this since 2014. HTX showed 38 consecutive months of 100% reserve ratios in their 2025 report.

It’s real progress. But Bithumb just exposed its limits.

The ghost Bitcoin never touched the blockchain. A standard PoR audit would have shown Bithumb’s on-chain holdings were correct. The problem was that the internal ledger briefly showed liabilities massively exceeding those reserves, and the system allowed those phantom balances to trade.

Nic Carter, a leading voice on PoR methodology, has noted that point-in-time attestations prove very little. Even daily audits don’t solve this. The issue isn’t whether reserves matched liabilities during a scheduled check. It’s that Bithumb’s systems credited balances without checking reserves at all, and those balances became market-active in minutes.

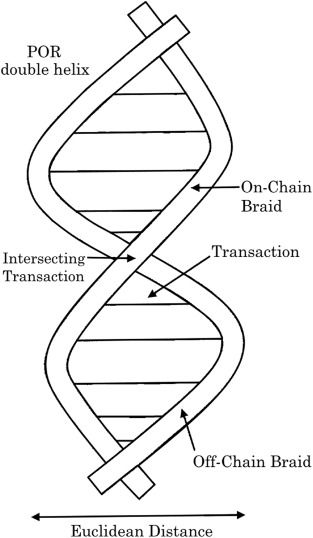

Proposals like the Double-Helix Framework (2025) and Chainlink’s real-time PoR feeds try to address this with continuous verification. But they require exchanges to fundamentally redesign how internal ledgers interact with on-chain settlement, an overhaul most platforms haven’t started. And if an exchange can credit balances in its database without blockchain settlement, real-time oracles can’t stop it.

The fundamental problem is architectural.

As long as CEXs operate on internal ledgers that update independently from blockchain settlement, what users see and what actually exists can diverge. PoR tells you the gap wasn’t there during the audit. It doesn’t tell you the gap can’t open between audits.

What This Means for Crypto’s Next Phase

Bithumb’s incident was operationally contained. But it’s strategically revealing.

The crypto industry is at an inflection point. Institutional adoption is accelerating. Spot Bitcoin ETFs in the U.S. crossed $100 billion in assets within their first year. Tokenized real-world assets are being explored by BlackRock, Fidelity, and traditional finance giants.

Regulators globally are moving from “ban it” to “regulate it.” The European Union’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation took full effect in 2024. The U.S. is debating stablecoin legislation. South Korea is on its second phase of digital asset law.

All of that regulatory and institutional momentum rests on an assumption: that centralized exchanges, the primary on-ramps to crypto for billions of users, can be made safe, transparent, and structurally sound with the right oversight.

Bithumb just showed that assumption is shakier than anyone wants to admit.

The exchange didn’t collapse. Users didn’t lose funds permanently. The blockchain continued operating exactly as designed.

But for twenty minutes, a major regulated platform in a developed economy with active financial supervision created $44 billion in assets it didn’t have, allowed those assets to trade against real liquidity, and only stopped the process because someone caught it manually.

That’s not a cybersecurity failure. It’s not a rogue actor. It’s not even fraud in the traditional sense. It’s a system operating exactly as designed, and the design is broken.

Bithumb CEO Lee Jae-won issued a public apology and committed to forming an internal task force to strengthen operational systems. The platform announced it will create a 100 billion won customer protection fund (~$68 million) to act as a buffer against future operational errors. It’s offering 110% compensation to users who sold Bitcoin at depressed prices, crediting 20,000 won to every user who logged in during the incident, and suspending trading fees across all listings for seven days.

None of that fixes the ledger problem.

South Korea’s regulatory response is the most substantive part of this story.

The FSS is not treating this as a one-off mistake. It’s treating it as a systemic risk signal that requires examining the internal mechanics of how exchanges validate balances, manage promotional systems, and segregate operational controls. Other jurisdictions should be watching closely.

Because if a platform the size of Bithumb, regulated, established, operating in one of the world’s most sophisticated financial markets, can briefly credit 3% of Bitcoin’s total supply without its systems objecting, the question isn’t whether this will happen again.

The question is where, and whether the next time will involve an asset less transparent than Bitcoin, or an exchange less capable of rapid manual intervention.

The Hard Question Nobody Wants to Answer

The crypto community’s default response to incidents like this: “not your keys, not your coins.” If you keep assets on an exchange instead of self-custodying, you’re taking a known risk.

That’s technically correct and strategically useless.

The overwhelming majority of crypto users, new entrants, institutions, active traders, are not going to self-custody.

Centralized exchanges provide fiat on-ramps, liquidity, derivatives, and institutional interfaces. They’re infrastructure. Telling people to “just self-custody” is like telling them to run their own email server. Technically possible. Practically irrelevant.

If crypto is going to scale, CEXs have to work. They have to be transparent and structurally sound. Right now, they’re not.

The Bithumb incident is a warning shot. Bitcoin’s supply didn’t change. The blockchain didn’t break. But the layer most users interact with just demonstrated it can create phantom assets at scale, and manual oversight was the only brake.

That’s not robust infrastructure. That’s a system running on trust in an industry built to eliminate trust.

The next time this happens, and there will be a next time, we might not get twenty minutes to catch it. We might get a cascade failure that triggers withdrawals an exchange can’t fulfill because its ledger diverged from reserves weeks earlier and nobody checked.

South Korean regulators understand this. The emergency task force, the licensing warnings, the legislative action, those aren’t overreactions. They’re the start of a reckoning about what “reserve-backed” means when reserves live on a blockchain but balances live in a database.

The ghost Bitcoin is gone. The vulnerability that created it is still here.

Until the industry admits that Proof of Reserves is necessary but insufficient, and that internal ledger architecture is a first-class security problem, the next Bithumb is already waiting to happen.