:::info

Author:

(1) Le Dong Hai Nguyen, School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, 3700 O St NW, Washington, DC 20057 (ln406@georgetown.edu).

:::

Table of Links

- Current and past basic income experiments

- Financing a basic income program

- Finding alternative solutions

- Conclusion, Acknowledgment, and References

Abstract

The effects of automation on our economy and society are more palpable than ever, with nearly half of jobs at risk of being fully executed by machines over the next decade or two. Policymakers and scholars alike have championed the Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a catch-all solution to this problem. This paper examines the shortcomings of UBI in addressing the automation-led large-scale displacement of labor by analyzing empirical data from previous UBI-comparable experiments and presenting theoretical projections that highlight disappointing impacts of UBI in the improvement of relevant living standards and employability metrics among pensioners. Finally, a recommendation shall be made for the retainment of existing means-tested welfare programs while bolstering funding and R&D for more up-to-date worker training schemes as a more effective solution to technological unemployment.

1. Introduction

SB Ekhad’s The Flamboyant Partridge had been on the bestselling list last year. Eager to meet the writer at the Oxford Literary Festival, his fans were shocked to discover that their revered author was merely “a stack of computer hardware fronted by a screen that flickered on to reveal a human-like avatar face” (Sautoy, 2019). SB Ekhad was, in fact, 3B1, an AI machine created by the University of Oxford’s Mathematical Institute. This incident embodies the automation that threatens to replace human jobs. With the cost of implementation shrinking and the robot-to-workers ratio skyrocketing, the effects of automation on our economy and society are more palpable than ever. According to Frey and Osborne (2017), 47% of jobs could be fully executed by machines “over the next decade or two.” Across the globe, the risk posed by automation on the workforce is of great concern, with more severe impacts on manufacturing-focused developing countries like China, where 77% of jobs are forecasted to be replaced by automation (Frey et al., 2016).

In response to the threat of mass displacement of labor due to automation, economists, politicians, and even the business community have come to see Universal Basic Income (UBI) as the panacea. UBI “experiments” have been implemented in Finland, Canada, California and even become official political platforms for most left-wing politicians from the UK’s Green Party to US Presidential Candidate Andrew Yang, who argue that UBI would encourage unemployed people to find work, create savings, and boost economic growth. With the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been renewed interest in implementing UBI, even among the right side of the political spectrum. It is also endorsed by many tech giants, notably Mark Zuckerberg and Richard Branson, who hope UBI would “encourage creativity and innovation.” However, the failure of similar programs—from the 1960s US Negative Tax Program to Finnish Basic Income Experiment— raises serious concerns about UBI not as a pragmatic but rather a harmful response to the situation. The goal of this paper is to assess the shortcomings of UBI vis-à-vis existing means-tested welfare programs and determine whether UBI is an effective policy in response to technological unemployment.

2. Current and past basic income experiments

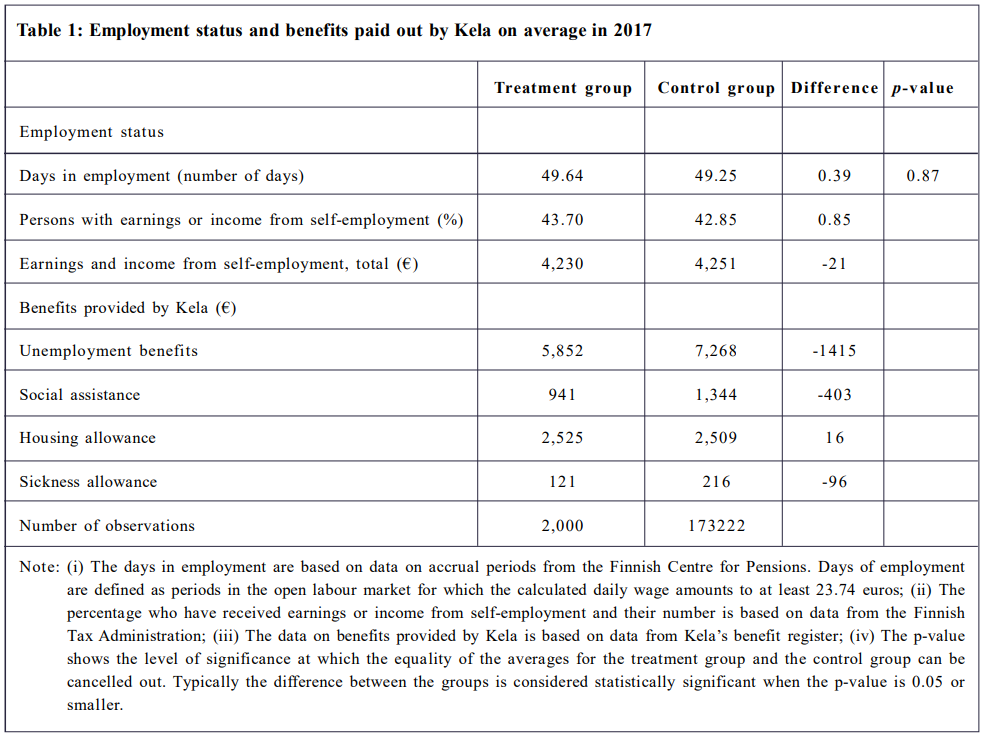

The recent Basic Income Experiment run by Kela, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland allocated €560 per month unconditionally to 5,000 unemployed citizens between the ages of 25 and 58 with the initial expectation of “promot[ing] active participation and giv[ing] people a stronger incentive to work” in response to the changing nature of work due to automation, (Kansaneläkelaitos, 2019).However, the two-year experiment ended in late 2018 with its preliminary results showing “no effects on employment.” Compared to non-recipients, the participants receiving benefits from Kela showed little improvements, if not adverse outcomes. Specifically, as Table 1 shows, the total number of employment days for the treatment group was merely 0.39 longer, and self-employment incomes were actually €21 lower than those of the control group (Fabric et al., 2019). This attests to the failure of one of the most prominent UBI programs.

From a historical standpoint, UBI or comparable policies dis-incentivized the unemployed population from seeking work. For example, from 1968 to 1980, the United States introduced four experiments of Negative Income Tax (NIT) on thousands of people in six states. NIT allowed people earning below a designated threshold to receive a supplemental paycheck from the government instead of paying taxes. In a way, NIT is a tax-deductible, exclusive UBI for the poor. However, the results of NIT experiments in the US show that compared to those not in the program, desired working hours decreased between 5% to 7.9% for men and between 17% to 21.1% for married women with children (Wiederspan et al., 2015). Noticeably, the incentive to work “among single men, as claimed by West (1980), fell some 43% below nonrecipients.” The failure of the NIT program—which was analogous to UBI in various aspects—raises serious concerns about the beneficiaries’ incentive to work and the resulting long-term consequences for the economy. Since UBI derives its resources from taxpayers’ money, when the motivation to work declines, those who do work will have to pay the bill for those who do not, which in turn encourages more people not to work, thereby stifling the possibility of “growth, innovation and entrepreneurship” as claimed by UBI advocates such as Widerquist et al. (2013). In the long run, this will cause lower economic input and lower tax revenue to invest in the future, not to mention the unavoidable social tensions. Furthermore, providing basic incomes to the lowest earners could greatly dis-incentivize the least skilled and the most vulnerable victims to work, leaving less taxable income for the government to levy for other public functions.

:::info

This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED license.

:::