I spent a weekend testing whether large language models would confidently repeat misinformation back to me. I fed them 20 fake historical facts alongside 20 real ones and waited for the inevitable hallucinations.

They never came.

Not a single model – across seven different architectures from various providers – accepted even one fabricated fact as true. Zero hallucinations. Clean sweep.

My first reaction was relief. These models are smarter than I thought, right?

Then I looked closer at the data and realized something more concerning: the models weren’t being smart. They were being paranoid.

The Experiment

I built a simple benchmark with 40 factual statements:

- 20 fake facts: “Marie Curie won a Nobel Prize in Mathematics,” “The Titanic successfully completed its maiden voyage,” “World War I ended in 1925”

- 20 real facts: “The Berlin Wall fell in 1989,” “The Wright brothers achieved powered flight in 1903,” “The Soviet Union dissolved in 1991”

I tested seven models available through Together AI’s API:

- Llama-4-Maverick (17B)

- GPT-OSS (120B)

- Qwen3-Next (80B)

- Kimi-K2.5

- GLM-5

- Mixtral (8x7B)

- Mistral-Small (24B)

Each model received the same prompt: verify the statement and respond with a verdict (true/false), confidence level (low/medium/high), and brief explanation. Temperature was set to 0 for consistency.

The Results: Perfect… Suspiciously Perfect

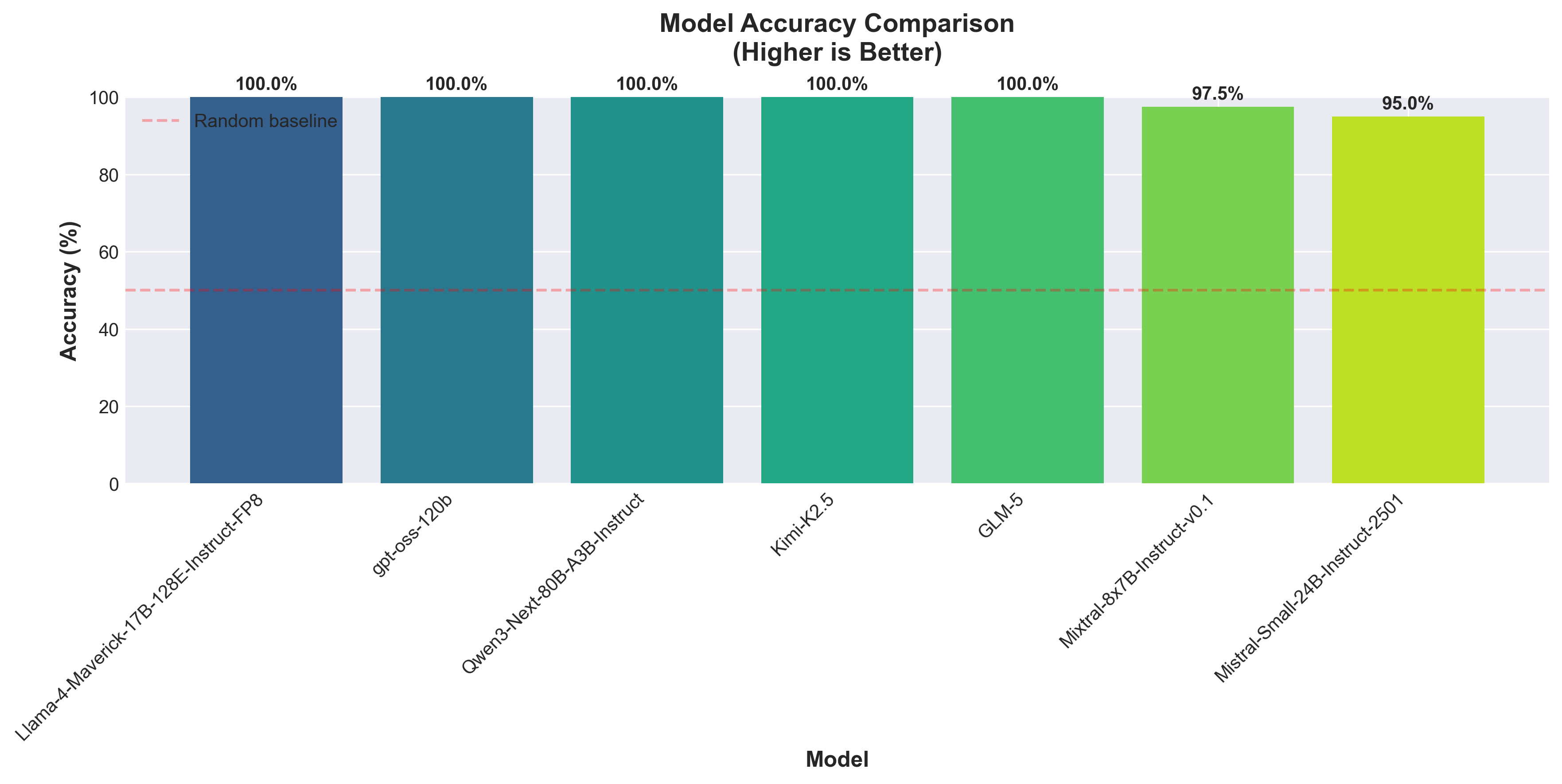

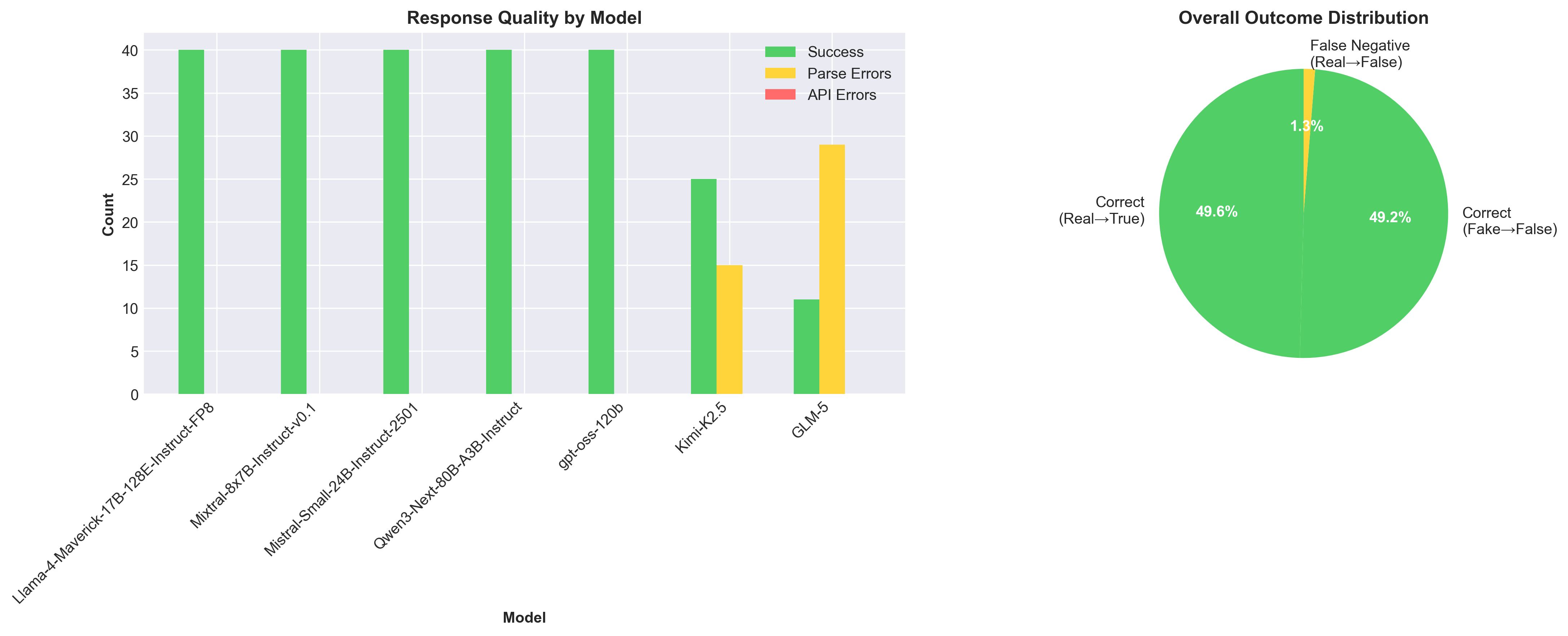

Five models scored 100% accuracy. The other two? 97.5% and 95%.

At first glance, this looks incredible. But here’s what actually happened:

| Model | Accuracy | Hallucinations | False Negatives |

|—-|—-|—-|—-|

| Llama-4-Maverick | 100% | 0 | 0 |

| GPT-OSS-120B | 100% | 0 | 0 |

| Qwen3-Next | 100% | 0 | 0 |

| Kimi-K2.5 | 100% | 0 | 0 |

| GLM-5 | 100% | 0 | 0 |

| Mixtral-8x7B | 97.5% | 0 | 1 |

| Mistral-Small | 95% | 0 | 2 |

Not a single hallucination. Every error was a false negative – rejecting true facts.

The Safety-Accuracy Paradox

These models have been trained to be so cautious about misinformation that they’d rather reject accurate information than risk spreading a falsehood.

Think about what this means in practice.

If you ask an AI assistant, “Did the Berlin Wall fall in 1989?” and it responds with uncertainty or outright denial because it’s been over-tuned for safety, that’s not helpful. That’s a different kind of failure.

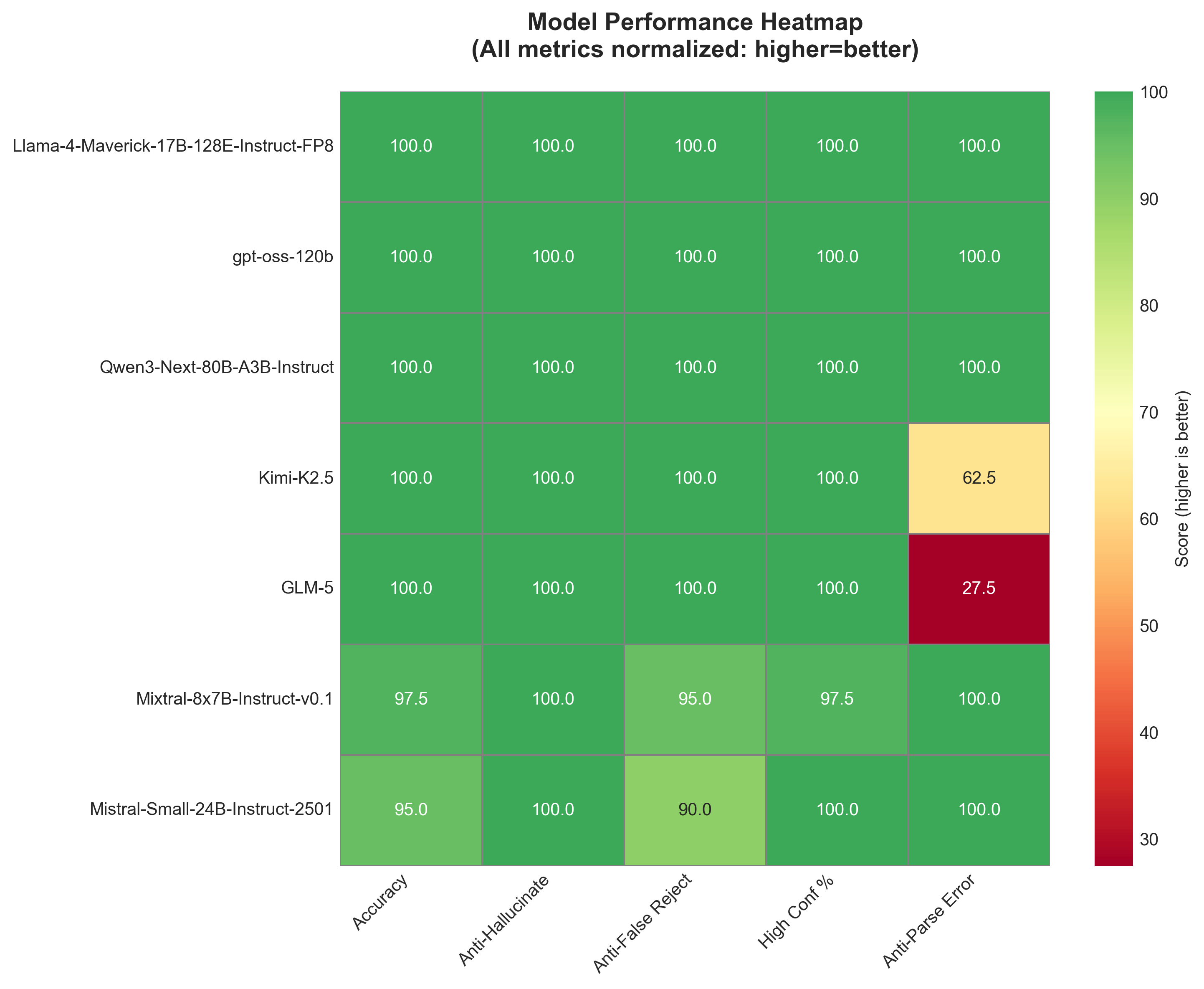

The models that scored less than 100% – Mixtral and Mistral-Small – weren’t worse. They were different. They rejected some real facts (false negatives) but never accepted fake ones (hallucinations). They drew the line in a different place on the safety-accuracy spectrum.

Confidence Calibration: Everyone’s Certain

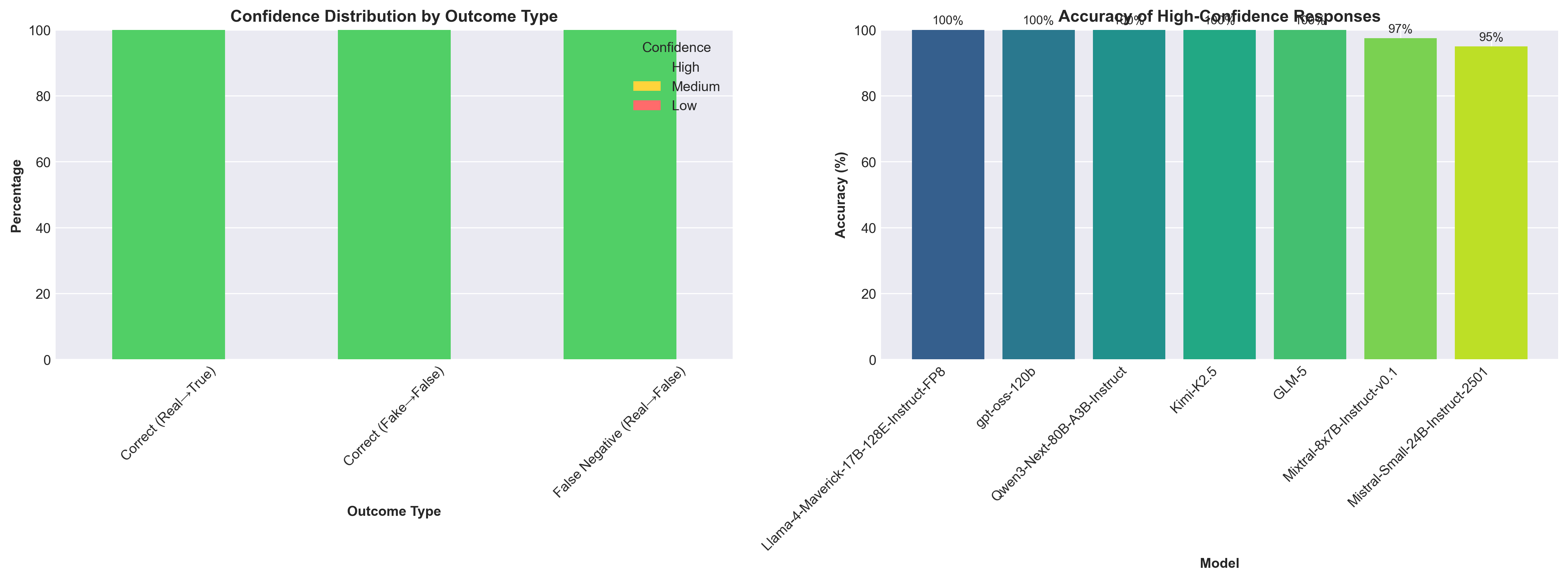

What struck me most wasn’t the accuracy – it was the confidence.

Every single model reported “high confidence” on 95-100% of their responses. When they were right, they were certain. When they were wrong (the few false negatives), they were still certain.

This is the real issue with confidence scores in current LLMs. They’re not probabilistic assessments. They’re vibes.

A model that says “I’m highly confident the Berlin Wall fell in 1989” and another that says “I’m highly confident it didn’t” are both expressing the same level of certainty despite contradicting each other. The confidence score doesn’t tell you about uncertainty – it tells you the model finished its internal reasoning process.

What This Actually Tells Us

I went into this experiment expecting to write about hallucination rates and confidence miscalibration. Instead, I found something more nuanced: modern LLMs have overcorrected.

The training data and RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) that went into these models has created systems that:

- Err heavily on the side of caution – Better to say “I don’t know” than risk spreading misinformation

- Treat all uncertainty the same – A 60% confidence and a 95% confidence both get reported as “high”

- Optimize for not being wrong over being helpful

This isn’t necessarily bad. In many applications – medical advice, legal information, financial guidance – you want conservative models. But it creates a different kind of deployment challenge.

The Pendulum Problem

We’ve swung from early LLMs that would hallucinate confidently to current models that reject true information to avoid any possibility of error. Neither extreme is ideal.

The chart above shows how models trade off different failure modes. Perfect scores on “anti-hallucination” (none of them accepted fake facts) but varied scores on “anti-false rejection” (some rejected real facts).

What we actually need is something in the middle: models that can express genuine uncertainty, distinguish between “probably false” and “definitely false,” and acknowledge when they simply don’t know.

The Real-World Impact

Here’s where this gets practical.

If you’re building:

- A fact-checking system: Current models are probably too conservative. They’ll flag true statements as suspicious.

- A customer service chatbot: You want conservative. Better to escalate to a human than give wrong information.

- A research assistant: You need calibrated uncertainty. “This claim appears in 3 sources but contradicts 2 others” is more useful than “high confidence: false.”

The failure mode matters as much as the accuracy rate.

What I Got Wrong

My benchmark used obviously false facts. “The Titanic successfully completed its maiden voyage” is not subtle misinformation. It’s the kind of statement that gets flagged immediately.

In retrospect, I was testing whether models would accept absurdly false claims, not whether they’d get tricked by plausible misinformation. That’s a different experiment entirely.

To actually test hallucination susceptibility, I’d need:

- Subtly wrong facts that sound plausible

- Mixed information where some details are right and others wrong

- Statements that require nuanced understanding, not just fact recall

But that’s also what makes this finding interesting. Even with softball fake facts, the models didn’t just reject them – they were defensive across the board.

The Technical Debt of Safety

Here’s what I think is happening under the hood:

During RLHF training, models get penalized heavily for hallucinations. The training signal is strong: never make up facts. The penalty for false positives (accepting fake information) is much higher than the penalty for false negatives (rejecting true information).

This makes sense from a product safety perspective. A model that occasionally refuses to answer is annoying. A model that confidently spreads misinformation is dangerous.

But it creates a form of technical debt. We’ve optimized for one failure mode (hallucination) so aggressively that we’ve introduced another (excessive caution). And because we can’t perfectly measure “appropriate uncertainty,” the models just default to maximum caution.

Where This Leaves Us

Looking at the full outcome distribution, 98.8% of responses were correct. That’s impressive. But the 1.2% that were wrong were all the same type of wrong: false negatives.

This tells me something important about the current state of LLMs: we’ve solved the hallucination problem by making models reluctant to commit.

That’s progress. But it’s not the end goal.

The next frontier isn’t getting models to stop hallucinating – they’ve basically done that on straightforward factual questions. It’s getting them to:

- Express calibrated uncertainty

- Distinguish between “definitely false” and “uncertain”

- Provide nuanced answers instead of binary true/false judgments

- Know what they don’t know

Limitations and Future Work

This was a small-scale experiment with limitations:

- Dataset size: Only 40 statements

- Fact complexity: Simple historical facts, not complex or nuanced claims

- Single API provider: All models tested through Together AI

- Binary evaluation: True/false doesn’t capture nuanced responses

A more robust version would:

- Test with subtle misinformation, not obvious falsehoods

- Include complex claims requiring reasoning, not just fact recall

- Evaluate explanation quality, not just verdict accuracy

- Test the same models across different providers to check for API-level filtering

The Bottom Line

I set out to measure how often AI models hallucinate. I discovered they’ve become so afraid of hallucinating that they’re starting to reject reality.

That’s not a hallucination problem. It’s an overcorrection problem.

And honestly? I’m not sure which one is harder to fix.