Table of Links

-

2.1 Text-to-Image Diffusion Model

2.3 Preliminary

2.3.1 Problem Statement

2.3.2 Assumptions

2.4 Methodology

2.4.1 Research Problem

2.4.2 Design Overview

2.4.3 Instance-level Solution

-

3.1 Settings

3.2 Main Results

3.3 Ablation Studies

3 Experimental Evaluation

In this section, we will first outline our experimental procedures. Then, we demonstrate if the proposed method can attain the objectives identified in Section 3.1. Finally, we complete an ablation study and discuss strategies for selecting optimal hyperparameters.

3.1 Settings

Text-to-image models. We use Stable Diffusion [17] with the Stable-Diffusion-v1-5 (SD-v1) [25] and Stable-Diffusion-v2-1 (SDv2) [26] checkpoints as the pre-trained models.

Datasets. We select two widely adopted caption-image datasets.

- CelebA-Dialog-HQ (CelebA) [9]: a large-scale visual-language face dataset with 30,000 high-resolution face images with the size of 1024×1024 selected from the CelebA dataset. Accompanied by each image, there is a caption that describes five fine-grained attributes including Bangs, Eyeglasses, Beard, Smiling, and Age.

2) Google’s Conceptual Captions (CC3M) [20]: a new dataset consisting of 3.3M images annotated with captions. We use its validation split which consists of 15,840 image/caption pairs. In contrast with the curated style of other image caption annotations, Conceptual Caption images and their descriptions are harvested from the web, and therefore represent a wider variety of styles.

Source model construction. We construct the source models by directly using pre-trained or consequently finetuning them on the above datasets. For the training data for finetuning, we randomly select 3000 samples from each dataset and resize them into 512×512. We finetune each pre-trained model on each dataset for a total of 3000 iterations with a constant learning rate of 2e-6 and batch size of 2. We denote these source models as: SD-v1, SD-v2, SD-v1-CelebA, SD-v2-CelebA, SD-v1-CC3M, SD-v2-CC3M.

Suspicious model construction. While pre-training and finetuning both raise concerns about IP infringement, fine-tuning has a more severe impact. Compared to pre-training, fine-tuning is highly convenient and efficient, allowing for many unauthorized uses without much resource restriction. Thus we built each infringing model by finetuning a pre-trained model on 500 training samples, where a proportion of 𝜌 of them are generated by a source model, while the rest are sampled from the real data. We follow the above pipeline to build the innocent models by setting 𝜌 = 0.

Baselines. Note that our work is the first to address the problem in training data attribution in the text-to-image scenario, and therefore, there is no directly related work. Hence, we have designed two methods to comprehensively demonstrate our effectiveness.

Baseline 1: Watermark-based data attribution. This baseline injects watermarks into the training data. More specifically, as proposed in [12], by encoding a unique 32-bit array into the images generated by the source models, the infringing models trained on such watermarked data will also generate images in which the watermark can be detected. We believe watermark-injection based method showcasing the best attribution ability.

Baseline 2: Random selection-based data attribution. This baseline adopts the similar idea with of our instance-level solution, but does

not use the Strategy 1 and Strategy 2 we proposed for data attribution. Specifically, we randomly select 𝑁 training samples from the source model’s training dataset as the attribution input. This serves as a baseline to demonstrate a straightforward attribution.

Evaluation Metrics. We use the Accuracy, Area Under Curve (AUC) score, and TPR@10%FPR [2] to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of the attribution methods. TPR@10%FPR measures the true-positive rate (TPR) at a low false-positive rate (FPR).

3.2 Main Results

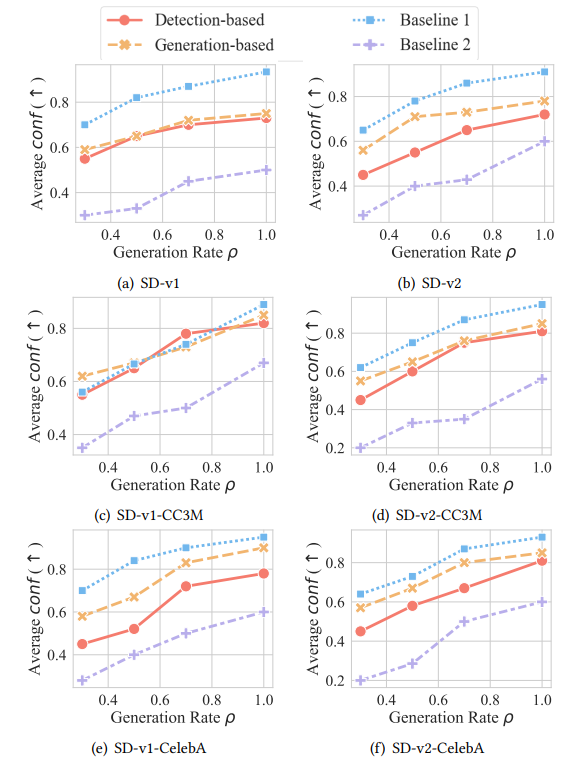

Effectiveness of Instance-level Attribution. Given each source model, we built 30 infringing models and calculated the conf metric defined in Equation 9 for each infringing model. Here we set the key sample size as 𝑁 = 30. To assess the reliability of our instance-level attribution solution, we report the average value of conf among the 30 infringing models under different generation rates 𝜌 in Figure 6. The infringing models are fine-tuned with increasing proportions of generated images (𝜌 = 30%, 50%, 70%, 100% out of a total of 500). The y-axis of Figure 6 refers to the average conf value. The higher the value, the more reliable our instance-level attribution solution is.

Main Result 1: Our solution surpasses Baseline 2, demonstrating a significant enhancement in attribution confidence by over 0.2 across diverse 𝜌 values. Concurrently, our generation-based strategy for attribution attains a reliability equivalent to that of Baseline 1, with a minimal decrease in confidence not exceeding 0.1.

Main Result 2: Our attribution method maintains its reliability even when the infringing model utilizes a small fraction of generated data for training. Our instance-level resolution, leveraging a generation-based strategy, exhibits a prediction confidence exceeding 0.6, even under a meager generation rate of 30%. This performance illustrates a marked advantage, with a 50% improvement over the baseline 2.

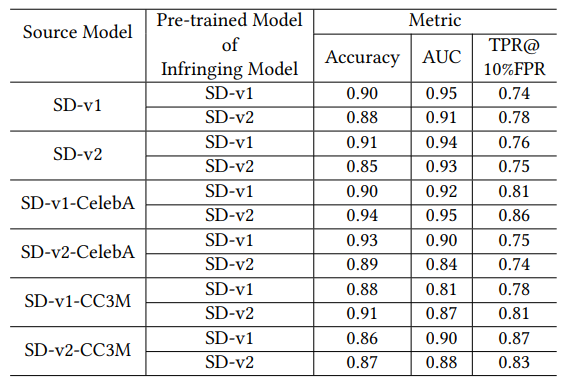

Effectiveness of Statistical-level Attribution. To train the discriminator model in Section 4.4, we set 𝑛 = 500, 𝑠 = 10, 𝑁 = 30. We evaluate the discriminator model and show the Accuracy, AUC, and TPR@10%FPR metrics in Table 1.

Main Result 3: Results in Table 1 show that our attribution achieves high accuracy and AUC performance, where the accuracy exceeds 85%, and AUC is higher than 0.8 for attributing infringing models to different source models. Accuracy and AUC are average-case metrics measuring how often an attribution method correctly predicts the infringement, while an attribution with a high FPR cannot be considered reliable. Thus we use TPR@10%FPR metric to evaluate the reliability of the statistical-level attribution. The rightmost column of Table 1 shows that TPR is over 0.7 at a low FPR of 10%. It means our attribution will not falsely assert an innocent model and is able to precisely distinguish the infringing models.

3.3 Ablation Studies

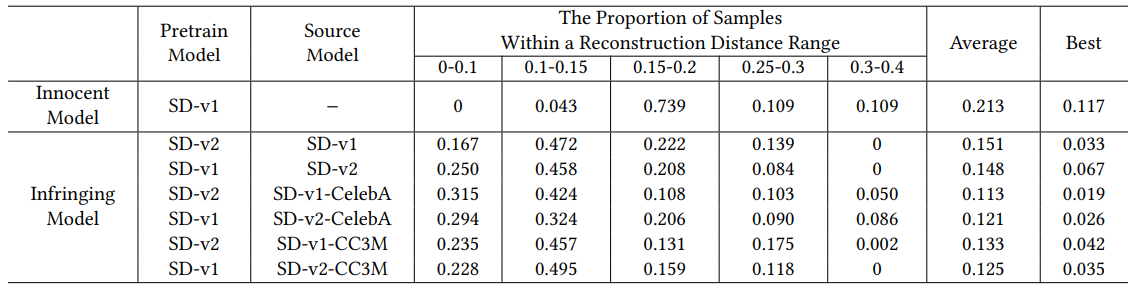

Effect of hyper-parameter 𝛿0. To determine an optimal value for 𝛿0 for the instance-level attribution, we calculate the reconstruction distance values using 30 key samples on an infringing model with 𝜌 = 1 and an innocent model with 𝜌 = 0. The innocent model is finetuned on the pre-trained model of SD-v2. Table 2 compares the reconstruction distance distribution across the suspicious models based on different source models. The columns 4-8 show the percentage of samples within a certain reconstruction distance range for each case, while the last 2 columns present the average and best reconstruction distance among all samples, respectively. The more

differences between the distributions of the innocent model and the infringing model, the easier to find a 𝛿0 for attribution.

For the innocent model, the reconstruction distance of a large proportion of samples (as large as 73.9%) falls within the range of [0.15,0.2), while only 4.3% samples have reconstruction distance smaller than 0.15. For the infringing model, there are about 20% samples have reconstruction distance smaller than 0.1. In most cases (5 out of 6 infringing models), over a proportion of 40% samples have the reconstruction distance within the range of [0.1,0.15). It indicates that 𝛿0 = 0.15 is a significant boundary for distinguishing innocent models and infringing models regardless of the source models. Hence, we set 𝛿0 = 0.15 in our experiments.

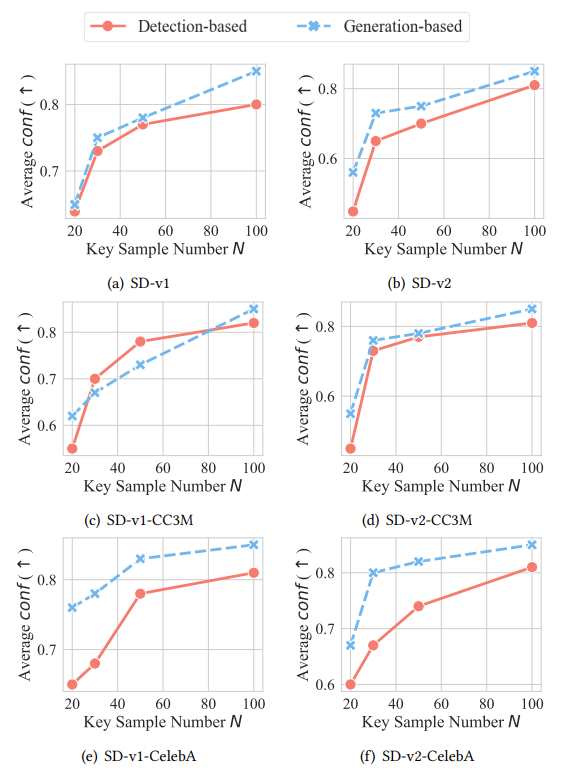

Effect of key sample size 𝑁. Following the settings in Table 2, we further study the impact of 𝑁 on the instance-level attribution, where 𝑁 ranges from 20 to 100 in Figure 7. The y-axis refers to the average value of conf on the 𝑁 key samples through Equation 6, where conf represents the attribution confidence to identify infringing models. Each sub-figure in Figure 7 represents an infringing model with the corresponding source model specified in the subtitle. The higher the confidence, the more reliable the attribution solution. Theoretically, an increasing 𝑁 improves the verification reliability but requires more queries to the suspicious model. Specifically, 𝑁 = 100 achieves the highest confidence, about 0.1 higher than that of 𝑁 = 30. However, such a number of queries cause larger costs and worse stealthiness during the verification process. 𝑁 = 30 has a similar performance as 𝑁 = 50, but it is dramatically better than 𝑁 = 20 with an advantage of about 0.1 when identifying the infringing models. Thus in our above experiments, we set 𝑁 = 30 for efficiency. In practice, the source model owner needs to make a trade-off between reliability and cost to set a suitable 𝑁.

3.4 Conclusion

This work tackles the crucial issue of training data attribution, investigating whether a suspicious model infringes on the intellectual property of a commercial model by using its generated data without authorization. Our proposed attribution solution allows for the identification of the source model from which a suspicious model’s training data originated. The rationale of our method lies in leveraging the inherent memorization property of training datasets, which will be passed down through generated data and preserved within models trained on such data. We devised algorithms to detect distinct samples that exhibit idiosyncratic behaviors in both source and suspicious models, exploiting these as inherent markers to trace the lineage of the suspicious model. Conclusively, our research provides a robust solution for user term violation detection in the domain of text-to-image models by enabling reliable origin attribution without altering the source model’s training or generation phase.

References

[1] Yossi Adi, Carsten Baum, Moustapha Cissé, Benny Pinkas, and Joseph Keshet. 2018. Turning Your Weakness Into a Strength: Watermarking Deep Neural Networks by Backdooring. In Proc. of USENIX Security Symposium.

[2] Nicholas Carlini, Steve Chien, Milad Nasr, Shuang Song, Andreas Terzis, and Florian Tramer. 2022. Membership inference attacks from first principles. In Proc. of IEEE S&P.

[3] Nicholas Carlini, Jamie Hayes, Milad Nasr, Matthew Jagielski, Vikash Sehwag, Florian Tramèr, Borja Balle, Daphne Ippolito, and Eric Wallace. 2023. Extracting Training Data from Diffusion Models. In Proc. of USENIX Security.

[4] Weixin Chen, Dawn Song, and Bo Li. 2023. TrojDiff: Trojan Attacks on Diffusion Models with Diverse Targets. In Proc. of IEEE CVPR.

[5] Sheng-Yen Chou, Pin-Yu Chen, and Tsung-Yi Ho. 2023. How to Backdoor Diffusion Models?. In Proc. of IEEE CVPR.

[6] Ge Han, Ahmed Salem, Zheng Li, Shanqing Guo, Michael Backes, and Yang Zhang. 2024. Detection and Attribution of Models Trained on Generated Data. In Proc. of IEEE ICASSP.

[7] ImagenAI. [n. d.]. https://imagen-ai.com/terms-of-use

[8] Hengrui Jia, Christopher A Choquette-Choo, Varun Chandrasekaran, and Nicolas Papernot. 2021. Entangled watermarks as a defense against model extraction. In Proc. of USENIX security.

[9] Yuming Jiang, Ziqi Huang, Xingang Pan, Chen Change Loy, and Ziwei Liu. 2021. Talk-to-Edit: Fine-Grained Facial Editing via Dialog. In Proc. of IEEE ICCV.

[10] Zongjie Li, Chaozheng Wang, Shuai Wang, and Cuiyun Gao. 2023. Protecting Intellectual Property of Large Language Model-Based Code Generation APIs via Watermarks. In Proc. of ACM CCS.

[11] Yugeng Liu, Zheng Li, Michael Backes, Yun Shen, and Yang Zhang. 2023. Watermarking diffusion model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12502 (2023).

[12] Ge Luo, Junqiang Huang, Manman Zhang, Zhenxing Qian, Sheng Li, and Xinpeng Zhang. 2023. Steal My Artworks for Fine-tuning? A Watermarking Framework for Detecting Art Theft Mimicry in Text-to-Image Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.13619 (2023).

[13] Peizhuo Lv, Hualong Ma, Kai Chen, Jiachen Zhou, Shengzhi Zhang, Ruigang Liang, Shenchen Zhu, Pan Li, and Yingjun Zhang. 2024. MEA-Defender: A Robust Watermark against Model Extraction Attack. In Proc. of IEEE S&P.

[14] MidJourney. [n. d.]. https://docs.midjourney.com/docs/terms-of-service

[15] Ed Pizzi, Sreya Dutta Roy, Sugosh Nagavara Ravindra, Priya Goyal, and Matthijs Douze. 2022. A Self-Supervised Descriptor for Image Copy Detection. In Proc. of IEEE/CVF CVPR.

[16] Aditya Ramesh, Prafulla Dhariwal, Alex Nichol, Casey Chu, and Mark Chen. 2022. Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125 (2022).

[17] Robin Rombach, Andreas Blattmann, Dominik Lorenz, Patrick Esser, and Björn Ommer. 2022. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proc. of IEEE CVPR.

[18] Olaf Ronneberger, Philipp Fischer, and Thomas Brox. 2015. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proc. of Springer MICCAI.

[19] Zeyang Sha, Xinlei He, Ning Yu, Michael Backes, and Yang Zhang. 2023. Can’t Steal? Cont-Steal! Contrastive Stealing Attacks Against Image Encoders. In Proc. of IEEE CVPR.

[20] Piyush Sharma, Nan Ding, Sebastian Goodman, and Radu Soricut. 2018. Conceptual Captions: A Cleaned, Hypernymed, Image Alt-text Dataset For Automatic Image Captioning. In Proc. of ACL.

[21] Reza Shokri, Marco Stronati, Congzheng Song, and Vitaly Shmatikov. 2017. Membership inference attacks against machine learning models. In 2017 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP). IEEE, 3–18.

[22] Gowthami Somepalli, Vasu Singla, Micah Goldblum, Jonas Geiping, and Tom Goldstein. 2023. Diffusion Art or Digital Forgery? Investigating Data Replication in Diffusion Models. In Proc. of IEEE CVPR.

[23] Gowthami Somepalli, Vasu Singla, Micah Goldblum, Jonas Geiping, and Tom Goldstein. 2023. Understanding and Mitigating Copying in Diffusion Models. In Proc. of NeurIPS.

[24] Lukas Struppek, Dominik Hintersdorf, and Kristian Kersting. 2022. Rickrolling the Artist: Injecting Invisible Backdoors into Text-Guided Image Generation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.02408 (2022).

[25] Stable-Diffusion v1 5. [n. d.]. https://huggingface.co/runwayml/stable-diffusionv1-5

[26] Stable-Diffusion v2 1. [n. d.]. https://huggingface.co/stabilityai/stable-diffusion2-1

[27] Yixin Wu, Rui Wen, Michael Backes, Ning Yu, and Yang Zhang. 2022. Model Stealing Attacks Against Vision-Language Models. (2022).

[28] Yunqing Zhao, Tianyu Pang, Chao Du, Xiao Yang, Ngai-Man Cheung, and Min Lin. 2023. A recipe for watermarking diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10137 (2023).

:::info

Authors:

(1) Likun Zhang;

(2) Hao Wu;

(3) Lingcui Zhang;

(4) Fengyuan Xu;

(5) Jin Cao;

(6) Fenghua Li;

(7) Ben Niu∗.

:::

:::info

This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 license.

:::

n