Table Of Links

- Memory Tagging Extension

- Speculative Execution Attack

4. Finding Tag Leakage Gadgets

- Tag Leakage Template

- Tag Leakage Fuzzing

- TIKTAG-v1: Exploiting Speculation Shrinkage

- TIKTAG-v2: Exploiting Store-to-Load Forwarding

6.1. Attacking Chrome

Real-World Attacks

To demonstrate the exploitability of TIKTAG gadgets in MTE-based mitigation, this section develops two realworld attacks against Chrome and Linux kernel (Figure 9). There are several challenges to launching real-world attacks using TIKTAG gadgets. First, TIKTAG gadgets should be executed in the target address space, requiring the attacker to construct or find gadgets from the target system. Second, the attacker should control and observe the cache state to leak the tag check results. In the following, we demonstrate the real-world attacks using TIKTAG gadgets on two real-world systems: the Google Chrome browser (§6.1) and the Linux kernel (§6.2), and discuss the mitigation strategies.

6.1. Attacking Chrome

Browser A web browser is a primary attack surface for webbased attacks as it processes untrusted web content, such as JavaScript and HTML. We first overview the threat model (§6.1.1) and provide a TIKTAG gadget constructed in the V8 JavaScript engine (§6.1.2). Then, we demonstrate the effectiveness of TIKTAG gadgets in exploiting the browser (§6.1.3) and discuss the mitigation strategies (§6.1.4).

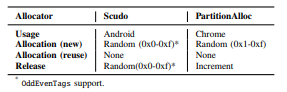

==6.1.1. Threat Model.== We follow the typical threat model of Chrome browser attacks, where the attacker aims to exploit memory corruption vulnerabilities in the renderer process. We assume the victim user visits the attacker-controlled website, which serves a malicious webpage. The webpage includes crafted HTML and JavaScript, which exploit memory corruption vulnerabilities in the victim’s renderer process. We assume all Chrome’s state-of-the-art mitigation techniques are in place, including ASLR [18], CFI [15], site isolation [53], and V8 sandbox [56]. Additionally, as an orthogonal defense, we assume that the renderer process enables random MTE tagging in PartitionAlloc [2].

==6.1.2. Constructing TIKTAG Gadget.== In the V8 JavaScript environment, TIKTAG-v2 was successfully constructed and leaked the MTE tags of any memory address. However, we didn’t find a constructible TIKTAG-v1 gadget, since the tight timing constraint between BR and CHECK was not feasible in our speculative V8 sandbox escape technique (§A).

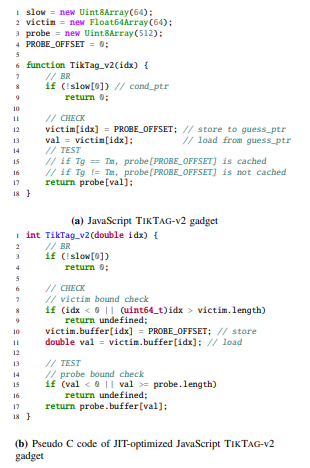

V8 TikTag-v2 Gadget. Figure 8 is the TIKTAG-v2 gadget constructed in the V8 JavaScript engine and its pseudo-C code after JIT compilation. With this gadget, the attacker can learn whether the guessed tag Tg matches with the tag Tm assigned to target_addr. The attacker prepares three arrays, slow, victim, probe, and an idx value. slow is a Unit8Array with a length of 64 and is accessed in BR to trigger the branch misprediction. victim is a Float64Array with length 64, which is accessed to trigger store-to-load forwarding. probe is a Uint8Array with length 512, and is accessed in

TEST to leak the tag check result. A Number type idx value is used in out-of-bounds access of victim. idx value is chosen such that victim[idx] points to targetaddr with a guessed tag Tg (i.e., (Tg«56)|targetaddr). To speculatively access the target_addr outside the V8 sandbox, we leveraged the speculative V8 sandbox escape technique we discovered during our research, which we detail in §A. Line 8 of Figure 8a is the BR block of the TIKTAG-v2 gadget, triggering branch misprediction with slow[0].

Line 12-13 is the CHECK block, which performs the store-to-load forwarding with victim[idx], accessing target_addr with a guessed tag Tg. When this code is JIT-compiled (Figure 8b), a bound check is performed, comparing idx against victim.length. If idx is an out-of-bounds index, the code returns undefined, but if victim.length field takes a long time to be loaded, the CPU speculatively executes the following store and load instructions.

After that, line 17 implements the TEST block, which accesses the probe with the forwarded value val as an index. Again, a bound check on val against the length of probe is preceded, but this check succeeds as PROBEOFFSET is smaller than the length of probe array. As a result, probe[PROBEOFFSET] is cached only when the store-to-load forwarding succeeds, which is the case when Tg matches Tm.

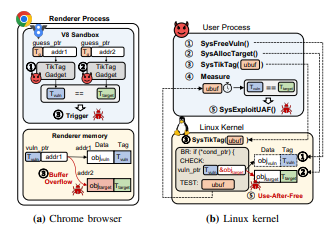

==6.1.3. Chrome MTE bypass attack.== Figure 9a illustrates the overall MTE bypass attack on the Chrome browser with arbitrary tag leakage primitive of TIKTAG gadgets. We assume a buffer overflow vulnerability in the renderer process, where exploiting a temporal vulnerability (e.g., use-after-free) is largely the same. The vulnerability overflows a pointer (i.e., vuln_ptr) to a vulnerable object (i.e., objvuln), corrupting the adjacent object (i.e., objtarget).

With PartitionAlloc’s MTE enforcement, two objects have different tags with a 14/15 probability. To avoid raising an exception, the attacker needs to ensure that the tags of objvuln and objtarget are the same. TIKTAG-v2 can be utilized to leak the tag of objvuln ( 1 ) and objtarget ( 2 ). If both leaked tags are the same, the attacker exploits the vulnerability, which would not raise a tag check fault ( 3 ). Otherwise, the attacker frees and re-allocates objtarget and goes back to the first step until the tags match.

==Triggering Cache Side-Channel.== To successfully exploit a TIKTAG gadget, the attacker needs to satisfy the following requirements:

i) branch training,

ii) cache control, and

iii) cache measurement. All three requirements can be met in JavaScript.

First, the attacker can train the branch predictor by running the gadget with non-zero slow[0] and in-bounds idx, and trigger the branch misprediction in BR with zero value in slow[0] and out-of-bounds idx.

Second, the attacker can evict the cache lines of slow[0], victim.length, and probe[PROBE_OFFSET] with JavaScript cache eviction techniques [8, 21, 70].

Third, the attacker can measure the cache status of probe[PROBE_OFFSET] with a high-resolution timer based on SharedArrayBuffer [16, 58].

==Exploiting Memory Corruption Vulnerabilities.== Given the leaked MTE tags, the attacker can exploit spatial and temporal memory corruption vulnerabilities in the renderer. The attack strategy is largely the same as the traditional memory corruption attacks but should ensure that the vulnerability does not raise a tag check fault utilizing the leaked tags. We further detail the attack strategy in §C.

==6.1.4. Mitigation.== To mitigate the TIKTAG gadget-based MTE bypass attacks in the browser renderer process, the following mitigations can be employed:

i) Speculative execution-aware sandbox: To stop attackers from launching TIKTAG-based attacks from a sandboxed environment like V8 sandbox, the sandbox can be fortified by preventing any speculative memory access beyond the sandbox’s memory region. While modern web browsers employ a sandbox to isolate untrusted web contents from the renderer, they often overlook speculative paths.

For instance, Chrome V8 sandbox [56] and Safari Webkit sandbox [1] do not completely mediate the speculative paths [27]. Based on current pointer compression techniques [64], speculative paths can be restricted to the sandbox region by masking out the high bits of the pointers.

ii) Speculation barrier: As suggested in §5, placing a speculation barrier after BR for potential TIKTAG gadgets can prevent speculative tag leakage attacks. However, this mitigation may not be applicable in the performance-critical browser environment, as it may introduce significant performance overhead.

iii) Prevention of gadget construction: As suggested in §5.2, the TIKTAG-v2 gadget can be mitigated by padding instructions between store and load instructions. A TIKTAGv1 gadget, although we have not found an exploitable one, can be mitigated by padding instructions between a branch and memory accesses, as described in §5.1.

6.2. Attacking the Linux Kernel

The Linux kernel on ARM is widely used for mobile devices, servers, and IoT devices, making it an attractive attack target. Exploiting a memory corruption vulnerability in the kernel can escalate the user’s privilege, and thus MTE is a promising protection mechanism for the Linux kernel. TIKTAG-based attacks against the Linux kernel pose unique challenges different from the browser attack (§6.1).

This is because the attacker’s address space is isolated from the kernel’s address space where the gadget will be executed. In the following, we first overview the threat model of the Linux kernel (§6.2.1) and provide a proof-of-concept TIKTAG gadget we discovered in the Linux kernel (§6.2.2). Finally, we demonstrate the effectiveness of TIKTAG gadgets in exploiting Linux kernel vulnerabilities (§6.2.3).

==6.2.1. Threat Model.== The threat model here is largely the same as that of typical privilege escalation attacks against the kernel. Specifically, we focus on the ARM-based Android Linux kernel, hardened with default kernel protections (e.g., KASLR, SMEP, SMAP, and CFI). We further assume the kernel is hardened with an MTE random tagging solution, similar to the production-ready MTE solutions, Scudo [3].

To be specific, each memory object is randomly tagged, and a random tag is assigned when an object is freed, thereby preventing both spatial and temporal memory corruptions. The attacker is capable of running an unprivileged process and aims to escalate their privilege by exploiting memory corruption vulnerabilities in the kernel. It is assumed that the attacker knows kernel memory corruption vulnerabilities but does not know any MTE tag of the kernel memory. Triggering memory corruption between kernel objects with

mismatching tags would raise a tag check fault, which is undesirable for real-world exploits. One critical challenge in this attack is that the gadget should be constructed by reusing the existing kernel code and executed by the system calls that the attacker can invoke. As the ARMv8 architecture separates user and kernel page tables, user space gadgets cannot speculatively access the kernel memory. This setup is very different from the threat model of attacking the browser (§6.1), which leveraged the attackerprovided code to construct the gadget. We excluded the eBPF-based gadget construction either [17, 28], because eBPF is not available for the unprivileged Android process [33].

==6.2.2. Kernel TikTag Gadget==. As described in §4.1, TIKTAG gadgets should meet several requirements, and each requirement entails challenges in the kernel environment.

First, in BR, a branch misprediction should be triggered with cond_ptr, which should be controllable from the user space. Since recent AArch64 processors isolate branch prediction training between the user and kernel [33], the branch training needs to be performed from the kernel space.

Second, in CHECK, guessptr should be dereferenced. guessptr should be crafted from the user space such that it embeds a guess tag (Tg) and points to the kernel address (i.e., target_addr) to leak the tag (Tm). Unlike the browser JavaScript environment (§6.1), user-provided data is heavily sanitized in system calls, so it is difficult to create an arbitrary kernel pointer.

For instance, accessok() ensures that the user-provided pointer points to the user space, and the arrayindexnospec macro prevents speculative out-of-bounds access with the user-provided index. Thus, guessptr should be an existing kernel pointer, specifically the vulnerable pointer that causes memory corruption. For instance, a dangling pointer in use-after-free (UAF) or an out-of-bounds pointer in buffer overflow can be used. Lastly, in TEST, testptr should be dereferenced, and testptr should be accessible from the user space. To ease the cache state measurement, test_ptr should be a user space pointer provided through a system call argument.

==Discovered Gadgets.== We manually analyzed the source code of the Linux kernel to find the TIKTAG gadget meeting the aforementioned requirements. As a result, we found one potentially exploitable TIKTAG-v1 gadget in sndtimeruserread() (Figure 10). This gadget fulfills the requirements of TIKTAG-v1 (§5.1). At line 10 (i.e., BR), the switch statement triggers branch misprediction with a user-controllable value tu->tread (i.e., condptr). At lines 14-17 (i.e., CHECK), tread (i.e., guessptr) is dereferenced by four load instructions. tread points to a struct sndtimer_tread64 object that the attacker can arbitrarily allocate and free.

If a temporal vulnerability transforms tread into a dangling pointer, it can be used as a guessptr. At line 20, (i.e., TEST), a user space pointer buffer (i.e., testptr) is dereferenced in copytouser. As this gadget is not directly reachable from the user space, we made a slight modification to the kernel code; we removed the early return for the default case at line 6. This ensures that the buffer is only accessed in the speculative path to observe the cache state difference due to speculative execution.

Although this modification is not realistic in a realworld scenario, it demonstrates the potential exploitability of the gadget if similar code changes are made. We discovered several more potentially exploitable gadgets, but we were not able to observe the cache state difference between the tag match and mismatch. Still, we think there is strong potential for exploiting those gadgets. Launching TIKTAG-based attacks involves complex and sensitive engineering, and thus we were not able to experiment with all possible cases.

Especially, TIKTAG-v1 relies on the speculation shrinkage on wrong path events, which may also include address translation faults or other exceptions in the branch misprediction path. As system calls involve complex control flows, the speculation shrinkage may not be triggered as expected. In addition, several gadgets may become exploitable when kernel code changes. For instance, a TIKTAG-v1 gadget in ip6mr_ioctl() did not exhibit an MTE tag leakage behavior when called from its system call path (i.e., ioctl). However, the gadget had tag leakage when it was ported to other syscalls (e.g., write) with a simple control flow.

==6.2.3. Kernel MTE bypass attack.== Figure 9b illustrates the MTE bypass attacks on the Linux kernel. Taking a use-afterfree vulnerability as an example, we assume the attacker has identified a corresponding TIKTAG gadget, SysTikTagUAF(), capable of leaking the tag check result of the dangling pointer created by the vulnerability. For instance, the TIKTAG-v1 gadget in sndtimeruser_read() (Figure 10) can leak the tag check result of tread, which can become a dangling pointer by a use-after-free or double-free vulnerability.

The attack proceeds as follows: First, the attacker frees a kernel object (i.e., objvuln) and leaves its pointer (i.e., vuln_ptr) as a dangling pointer ( 1 ). Next, the attacker allocates another kernel object (i.e., objtarget) at the address of objvuln with SysAllocTarget() ( 2 ). Then, the attacker invokes SysTikTag() with a user space buffer (i.e., ubuf) ( 3 ), and leaks the tag check result (i.e., Tm == Tg) by measuring the access latency of ubuf ( 4 ). If the tags match, the attacker triggers SysExploitUAF(), a system call that exploits the use-after-free vulnerability ( 5 ). Otherwise, the attacker reallocates objtarget until the tags match.

==Triggering Cache Side-Channel.== As in §6.1.3, a successful TIKTAG gadget exploitation requires i) branch training, ii) cache control, and iii) cache measurement. For branch training, the attacker can train the branch predictor and trigger speculation with user-controlled branch conditions from the user space. For cache control, the attacker can flush the user space buffer (i.e., ubuf), while the kernel memory address can be evicted by cache line bouncing [25]. For cache measurement, the access latency of ubuf can be measured with the virtual counter (i.e., CNTVCT_EL0) or a memory counter-based timer (i.e., near CPU cycle resolution).

==Exploiting Memory Corruption Vulnerabilities.== TIKTAG gadgets enable bypassing MTE and exploiting kernel memory corruption vulnerabilities. The attacker can invoke the TIKTAG gadget in the kernel to speculatively trigger the memory corruption and obtain the tag check result. Then, the attacker can obtain the tag check result, and trigger the memory corruption only if the tags match. We detail the Linux kernel MTE bypass attack process in §D.

==6.2.4. Mitigation.== To mitigate TIKTAG gadget in the Linux kernel, the kernel developers should consider the following mitigations:

i) Speculation barrier: Speculation barriers can effectively mitigate TIKTAG-v1 gadget in the Linux kernel. To prevent attackers from leaking the tag check result through the user space buffer, kernel functions that access user space addresses, such as copytouser and copyfromuser, can be hardened with speculation barriers. As described in §5.1, leaking tag check results with store access can be mitigated by placing a speculation barrier before the store access (i.e., TEST).

For instance, to mitigate the gadgets leveraging copytouser, a speculation barrier can be inserted before the copytouser invocation. For gadgets utilizing load access to the user space buffer, the barriers mitigate the gadgets if inserted between the branch and the kernel memory access (i.e., CHECK). For instance, to mitigate the gadgets leveraging copyfromuser, the kernel developers should carefully analyze the kernel code base to find the pattern of the conditional branch, kernel memory access, and copyfromuser(), and insert a speculation barrier between the branch and the kernel memory access.

ii) Prevention of gadget construction: To eliminate potential TIKTAG gadgets in the Linux kernel, the kernel source code can be analyzed and patched. As TIKTAG gadgets can also be constructed by compiler optimizations, a binary analysis can be conducted. For each discovered gadget, instructions can be reordered or additional instructions can be inserted to prevent the gadget construction, following the mitigation strategies in §5.1 and §5.2.

:::info

Authors:

:::

:::info

This paper is available on arxiv under CC 4.0 license.

:::